Tabla periódica

Definición

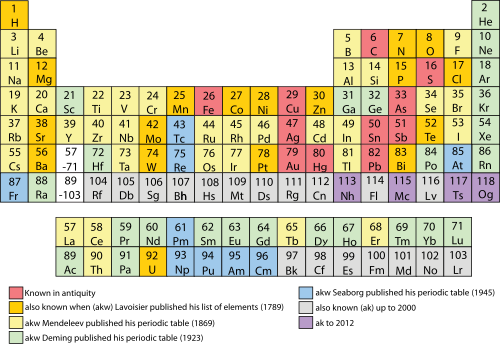

La tabla periódica es una disposición tabular de los elementos químicos, ordenados por su número atómico, configuración de electrones y propiedades químicas recurrentes, cuya estructura muestra tendencias periódicas . Generalmente, dentro de una fila (período) los elementos son metales a la izquierda y no metales a la derecha, con los elementos que tienen comportamientos químicos similares colocados en la misma columna. Las filas de la tabla se denominan comúnmente períodos y las columnas se llaman grupos. Seis grupos han aceptado nombres así como números asignados: por ejemplo, los elementos del grupo 17 son los halógenos; y el grupo 18 son los gases nobles. También se muestran cuatro áreas rectangulares simples o bloques asociados con el llenado de diferentes orbitales atómicos.

La organización de la tabla periódica puede usarse para derivar relaciones entre las diversas propiedades de elementos, pero también las propiedades químicas predichas y los comportamientos de elementos no descubiertos o recién sintetizados. El químico ruso Dmitri Mendeleev fue el primero en publicar una tabla periódica reconocible en 1869, desarrollada principalmente para ilustrar las tendencias periódicas de los elementos conocidos. También predijo algunas propiedades de elementos no identificados que se espera que llenen vacíos dentro de la tabla. La mayoría de sus pronósticos demostraron ser correctos. La idea de Mendeleev ha sido lentamente expandida y refinada con el descubrimiento o la síntesis de nuevos elementos adicionales y el desarrollo de nuevos modelos teóricos para explicar el comportamiento químico. La tabla periódica moderna ahora proporciona un marco útil para analizar las reacciones químicas,

All the elements from atomic numbers 1 (hydrogen) through 118 (oganesson) have been either discovered or synthesized, completing the first seven rows of the periodic table. The first 98 elements exist in nature, although some are found only in trace amounts and others were synthesized in laboratories before being found in nature. Elements 99 to 118 have only been synthesized in laboratories or nuclear reactors. The synthesis of elements having higher atomic numbers is currently being pursued: these elements would begin an eighth row, and theoretical work has been done to suggest possible candidates for this extension. Numerous synthetic radionuclides of naturally occurring elements have also been produced in laboratories.

Overview

Periodic table

| Group | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 | 8 | 9 | 10 | 11 | 12 | 13 | 14 | 15 | 16 | 17 | 18 | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Alkali metals | Alkaline earth metals | Pnictogens | Chalcogens | Halogens | Noble gases | ||||||||||||||

| Period 1 | |||||||||||||||||||

| 2 | |||||||||||||||||||

| 3 | |||||||||||||||||||

| 4 | |||||||||||||||||||

| 5 | |||||||||||||||||||

| 6 | |||||||||||||||||||

| 7 | |||||||||||||||||||

1 (rojo) = Gas 3 (negro) = Sólido 80 (verde) = Líquido 109 (gris) = Desconocido El color del número atómico muestra el estado de la materia (a 0 ° C y 1 atm)

Primordial

de la caries sintético Border muestra ocurrencia natural del elemento

de la caries sintético Border muestra ocurrencia natural del elemento

Peso atómico estándar ( A r )

- Ca: 40.078 - Valor corto formal, redondeado (sin incertidumbre)

- Po: [209] - número masivo del isótopo más estable

El color de fondo muestra una subcategoría en la tendencia metal-metaloide-no-metal:

| Metal | Metaloide | No metal | Propiedades químicasdesconocidas | |||||||

| Metal alcalino | Metal alcalinotérreo | Lantánido | Actínido | Metal de transición | Metal posterior a la transición | Reactivo no metálico | gas noble | |||

Cada elemento químico tiene un número atómico único ( Z ) que representa el número de protones en su núcleo. La mayoría de los elementos tienen diferentes números de neutrones entre diferentes átomos, y estas variantes se conocen como isótopos. Por ejemplo, el carbono tiene tres isótopos naturales: todos sus átomos tienen seis protones y la mayoría también tienen seis neutrones, pero aproximadamente un uno por ciento tiene siete neutrones, y una fracción muy pequeña tiene ocho neutrones. Los isótopos nunca se separan en la tabla periódica; siempre se agrupan bajo un solo elemento. Los elementos sin isótopos estables tienen las masas atómicas de sus isótopos más estables, donde se muestran dichas masas, enumeradas entre paréntesis.

En la tabla periódica estándar, los elementos se enumeran en orden de aumentar el número atómico Z (el número de protones en el núcleo de un átomo). Se inicia una nueva fila ( punto ) cuando un nuevo caparazón de electrones tiene su primer electrón. Columnas ( grupos) están determinados por la configuración electrónica del átomo; los elementos con el mismo número de electrones en una subcapa particular caen en las mismas columnas (por ejemplo, el oxígeno y el selenio están en la misma columna porque ambos tienen cuatro electrones en la subnúclea p más externa). Los elementos con propiedades químicas similares generalmente caen en el mismo grupo en la tabla periódica, aunque en el bloque f, y con cierto respeto en el bloque d, los elementos en el mismo período tienden a tener propiedades similares también. Por lo tanto, es relativamente fácil predecir las propiedades químicas de un elemento si se conocen las propiedades de los elementos que lo rodean.

As of 2016, the periodic table has 118 confirmed elements, from element 1 (hydrogen) to 118 (oganesson). Elements 113, 115, 117 and 118, the most recent discoveries, were officially confirmed by the International Union of Pure and Applied Chemistry (IUPAC) in December 2015. Their proposed names, nihonium (Nh), moscovium (Mc), tennessine (Ts) and oganesson (Og) respectively, were announced by the IUPAC in June 2016 and made official in November 2016.

The first 94 elements occur naturally; the remaining 24, americium to oganesson (95–118), occur only when synthesized in laboratories. Of the 94 naturally occurring elements, 83 are primordial and 11 occur only in decay chains of primordial elements. No element heavier than einsteinium (element 99) has ever been observed in macroscopic quantities in its pure form, nor has astatine (element 85); francium (element 87) has been only photographed in the form of light emitted from microscopic quantities (300,000 atoms).

Grouping methods

Groups

A group or family is a vertical column in the periodic table. Groups usually have more significant periodic trends than periods and blocks, explained below. Modern quantum mechanical theories of atomic structure explain group trends by proposing that elements within the same group generally have the same electron configurations in their valence shell. Consequently, elements in the same group tend to have a shared chemistry and exhibit a clear trend in properties with increasing atomic number. In some parts of the periodic table, such as the d-block and the f-block, horizontal similarities can be as important as, or more pronounced than, vertical similarities.

Under an international naming convention, the groups are numbered numerically from 1 to 18 from the leftmost column (the alkali metals) to the rightmost column (the noble gases).Previously, they were known by roman numerals. In America, the roman numerals were followed by either an "A" if the group was in the s- or p-block, or a "B" if the group was in the d-block. The roman numerals used correspond to the last digit of today's naming convention (e.g. the group 4 elements were group IVB, and the group 14 elements were group IVA). In Europe, the lettering was similar, except that "A" was used if the group was before group 10, and "B" was used for groups including and after group 10. In addition, groups 8, 9 and 10 used to be treated as one triple-sized group, known collectively in both notations as group VIII. In 1988, the new IUPAC naming system was put into use, and the old group names were deprecated.

Some of these groups have been given trivial (unsystematic) names, as seen in the table below, although some are rarely used. Groups 3–10 have no trivial names and are referred to simply by their group numbers or by the name of the first member of their group (such as "the scandium group" for group 3), since they display fewer similarities and/or vertical trends.

Elements in the same group tend to show patterns in atomic radius, ionization energy, and electronegativity. From top to bottom in a group, the atomic radii of the elements increase. Since there are more filled energy levels, valence electrons are found farther from the nucleus. From the top, each successive element has a lower ionization energy because it is easier to remove an electron since the atoms are less tightly bound. Similarly, a group has a top-to-bottom decrease in electronegativity due to an increasing distance between valence electrons and the nucleus.There are exceptions to these trends: for example, in group 11, electronegativity increases farther down the group.

Groups in the Periodic table

| IUPAC group | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 | 8 | 9 | 10 | 11 | 12 | 13 | 14 | 15 | 16 | 17 | 18 | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Mendeleev(I–VIII) | I | II | III | IV | V | VI | VII | VIII | I | II | III | IV | V | VI | VII | |||||

| CAS (US, A-B-A) | IA | IIA | IIIB | IVB | VB | VIB | VIIB | VIIIB | IB | IIB | IIIA | IVA | VA | VIA | VIIA | VIIIA | ||||

| old IUPAC(Europe, A-B) | IA | IIA | IIIA | IVA | VA | VIA | VIIA | VIII | IB | IIB | IIIB | IVB | VB | VIB | VIIB | 0 | ||||

| Trivial name | Alkali metals | Alkaline earth metals | Coinage metals | Triels | Tetrels | Pnictogens | Chalcogens | Halogens | Noble gases | |||||||||||

| Name by element | Lithium group | Beryllium group | Scandium group | Titanium group | Vanadium group | Chromium group | Manganese group | Iron group | Cobalt group | Nickel group | Copper group | Zinc group | Boron group | Carbon group | Nitrogen group | Oxygen group | Fluorine group | Helium orNeon group | ||

| Period 1 | H | He | ||||||||||||||||||

| Period 2 | Li | Be | B | C | N | O | F | Ne | ||||||||||||

| Period 3 | Na | Mg | Al | Si | P | S | Cl | Ar | ||||||||||||

| Period 4 | K | Ca | Sc | Ti | V | Cr | Mn | Fe | Co | Ni | Cu | Zn | Ga | Ge | As | Se | Br | Kr | ||

| Period 5 | Rb | Sr | Y | Zr | Nb | Mo | Tc | Ru | Rh | Pd | Ag | Cd | In | Sn | Sb | Te | I | Xe | ||

| Period 6 | Cs | Ba | La | Ce–Lu | Hf | Ta | W | Re | Os | Ir | Pt | Au | Hg | Tl | Pb | Bi | Po | At | Rn | |

| Period 7 | Fr | Ra | Ac | Th–Lr | Rf | Db | Sg | Bh | Hs | Mt | Ds | Rg | Cn | Nh | Fl | Mc | Lv | Ts | Og | |

Group 3 has scandium (Sc) and yttrium (Y). For the rest of the group, sources differ as either being (1) lutetium (Lu) and lawrencium (Lr), or (2) lanthanum (La) and actinium (Ac), or(3) the whole set of 15+15 lanthanides and actinides. IUPAC has initiated a project to standardize the definition as either (1) Sc, Y, Lu and Lr, or (2) Sc, Y, La and Ac.

Group 18, the noble gases, were not discovered at the time of Mendeleev's original table. Later (1902), Mendeleev accepted the evidence for their existence, and they could be placed in a new "group 0", consistently and without breaking the periodic table principle.

Group name as recommended by IUPAC.

Hydrogen (H), while placed in group 1, is not considered to be part of the alkali metals.

Group 18, the noble gases, were not discovered at the time of Mendeleev's original table. Later (1902), Mendeleev accepted the evidence for their existence, and they could be placed in a new "group 0", consistently and without breaking the periodic table principle.

Group name as recommended by IUPAC.

Hydrogen (H), while placed in group 1, is not considered to be part of the alkali metals.

Periods

A period is a horizontal row in the periodic table. Although groups generally have more significant periodic trends, there are regions where horizontal trends are more significant than vertical group trends, such as the f-block, where the lanthanides and actinides form two substantial horizontal series of elements.

Elements in the same period show trends in atomic radius, ionization energy, electron affinity, and electronegativity. Moving left to right across a period, atomic radius usually decreases. This occurs because each successive element has an added proton and electron, which causes the electron to be drawn closer to the nucleus. This decrease in atomic radius also causes the ionization energy to increase when moving from left to right across a period. The more tightly bound an element is, the more energy is required to remove an electron. Electronegativity increases in the same manner as ionization energy because of the pull exerted on the electrons by the nucleus. Electron affinity also shows a slight trend across a period. Metals (left side of a period) generally have a lower electron affinity than nonmetals (right side of a period), with the exception of the noble gases.

Blocks

Specific regions of the periodic table can be referred to as blocks in recognition of the sequence in which the electron shells of the elements are filled. Each block is named according to the subshell in which the "last" electron notionally resides. The s-block comprises the first two groups (alkali metals and alkaline earth metals) as well as hydrogen and helium. The p-blockcomprises the last six groups, which are groups 13 to 18 in IUPAC group numbering (3A to 8A in American group numbering) and contains, among other elements, all of the metalloids. The d-block comprises groups 3 to 12 (or 3B to 2B in American group numbering) and contains all of the transition metals. The f-block, often offset below the rest of the periodic table, has no group numbers and comprises lanthanides and actinides.

Metals, metalloids and nonmetals

According to their shared physical and chemical properties, the elements can be classified into the major categories of metals, metalloidsand nonmetals. Metals are generally shiny, highly conducting solids that form alloys with one another and salt-like ionic compounds with nonmetals (other than noble gases). A majority of nonmetals are coloured or colourless insulating gases; nonmetals that form compounds with other nonmetals, feature covalent bonding. In between metals and nonmetals are metalloids, which have intermediate or mixed properties.

Metal and nonmetals can be further classified into subcategories that show a gradation from metallic to non-metallic properties, when going left to right in the rows. The metals may be subdivided into the highly reactive alkali metals, through the less reactive alkaline earth metals, lanthanides and actinides, via the archetypal transition metals, and ending in the physically and chemically weak post-transition metals. Nonmetals may be simply subdivided into the polyatomic nonmetals, being nearer to the metalloids and show some incipient metallic character; the essentially nonmetallic diatomic nonmetals, nonmetallic and the almost completely inert, monatomic noble gases. Specialized groupings such as refractory metals and noble metals, are examples of subsets of transition metals, also known and occasionally denoted.

Placing elements into categories and subcategories based just on shared properties is imperfect. There is a large disparity of properties within each category with notable overlaps at the boundaries, as is the case with most classification schemes. Beryllium, for example, is classified as an alkaline earth metal although its amphoteric chemistry and tendency to mostly form covalent compounds are both attributes of a chemically weak or post-transition metal. Radon is classified as a nonmetallic noble gas yet has some cationic chemistry that is characteristic of metals. Other classification schemes are possible such as the division of the elements into mineralogical occurrence categories, or crystalline structures. Categorizing the elements in this fashion dates back to at least 1869 when Hinrichs wrote that simple boundary lines could be placed on the periodic table to show elements having shared properties, such as metals, nonmetals, or gaseous elements.

Periodic trends and patterns

Electron configuration

The electron configuration or organisation of electrons orbiting neutral atoms shows a recurring pattern or periodicity. The electrons occupy a series of electron shells (numbered 1, 2, and so on). Each shell consists of one or more subshells (named s, p, d, f and g). As atomic number increases, electrons progressively fill these shells and subshells more or less according to the Madelung rule or energy ordering rule, as shown in the diagram. The electron configuration for neon, for example, is 1s 2s 2p. With an atomic number of ten, neon has two electrons in the first shell, and eight electrons in the second shell; there are two electrons in the s subshell and six in the p subshell. In periodic table terms, the first time an electron occupies a new shell corresponds to the start of each new period, these positions being occupied by hydrogen and the alkali metals.

Since the properties of an element are mostly determined by its electron configuration, the properties of the elements likewise show recurring patterns or periodic behaviour, some examples of which are shown in the diagrams below for atomic radii, ionization energy and electron affinity. It is this periodicity of properties, manifestations of which were noticed well before the underlying theory was developed, that led to the establishment of the periodic law (the properties of the elements recur at varying intervals) and the formulation of the first periodic tables.

Atomic radii

Atomic radii vary in a predictable and explainable manner across the periodic table. For instance, the radii generally decrease along each period of the table, from the alkali metals to the noble gases; and increase down each group. The radius increases sharply between the noble gas at the end of each period and the alkali metal at the beginning of the next period. These trends of the atomic radii (and of various other chemical and physical properties of the elements) can be explained by the electron shell theory of the atom; they provided important evidence for the development and confirmation of quantum theory.

The electrons in the 4f-subshell, which is progressively filled across the lanthanide series, are not particularly effective at shielding the increasing nuclear charge from the sub-shells further out. The elements immediately following the lanthanides have atomic radii that are smaller than would be expected and that are almost identical to the atomic radii of the elements immediately above them. Hence hafnium has virtually the same atomic radius (and chemistry) as zirconium, and tantalum has an atomic radius similar to niobium, and so forth. This is known as the lanthanide contraction. The effect of the lanthanide contraction is noticeable up to platinum (element 78), after which it is masked by a relativistic effect known as the inert pair effect. The d-block contraction, which is a similar effect between the d-block and p-block, is less pronounced than the lanthanide contraction but arises from a similar cause.

Ionization energy

The first ionization energy is the energy it takes to remove one electron from an atom, the second ionization energy is the energy it takes to remove a second electron from the atom, and so on. For a given atom, successive ionization energies increase with the degree of ionization. For magnesium as an example, the first ionization energy is 738 kJ/mol and the second is 1450 kJ/mol. Electrons in the closer orbitals experience greater forces of electrostatic attraction; thus, their removal requires increasingly more energy. Ionization energy becomes greater up and to the right of the periodic table.

Large jumps in the successive molar ionization energies occur when removing an electron from a noble gas (complete electron shell) configuration. For magnesium again, the first two molar ionization energies of magnesium given above correspond to removing the two 3s electrons, and the third ionization energy is a much larger 7730 kJ/mol, for the removal of a 2p electron from the very stable neon-like configuration of Mg. Similar jumps occur in the ionization energies of other third-row atoms.

Electronegativity

Electronegativity is the tendency of an atom to attract a shared pair of electrons. An atom's electronegativity is affected by both its atomic number and the distance between the valence electrons and the nucleus. The higher its electronegativity, the more an element attracts electrons. It was first proposed by Linus Pauling in 1932. In general, electronegativity increases on passing from left to right along a period, and decreases on descending a group. Hence, fluorine is the most electronegative of the elements, while caesium is the least, at least of those elements for which substantial data is available.

There are some exceptions to this general rule. Gallium and germanium have higher electronegativities than aluminium and siliconrespectively because of the d-block contraction. Elements of the fourth period immediately after the first row of the transition metals have unusually small atomic radii because the 3d-electrons are not effective at shielding the increased nuclear charge, and smaller atomic size correlates with higher electronegativity. The anomalously high electronegativity of lead, particularly when compared to thallium and bismuth, appears to be an artifact of data selection and data availability. Methods of calculation other than the Pauling method show the normal periodic trends for these elements.

Electron affinity

The electron affinity of an atom is the amount of energy released when an electron is added to a neutral atom to form a negative ion. Although electron affinity varies greatly, some patterns emerge. Generally, nonmetals have more positive electron affinity values than metals. Chlorine most strongly attracts an extra electron. The electron affinities of the noble gases have not been measured conclusively, so they may or may not have slightly negative values.

Electron affinity generally increases across a period. This is caused by the filling of the valence shell of the atom; a group 17 atom releases more energy than a group 1 atom on gaining an electron because it obtains a filled valence shell and is therefore more stable.

A trend of decreasing electron affinity going down groups would be expected. The additional electron will be entering an orbital farther away from the nucleus. As such this electron would be less attracted to the nucleus and would release less energy when added. In going down a group, around one-third of elements are anomalous, with heavier elements having higher electron affinities than their next lighter congenors. Largely, this is due to the poor shielding by d and f electrons. A uniform decrease in electron affinity only applies to group 1 atoms.

Metallic character

The lower the values of ionization energy, electronegativity and electron affinity, the more metallic character the element has. Conversely, nonmetallic character increases with higher values of these properties. Given the periodic trends of these three properties, metallic character tends to decrease going across a period (or row) and, with some irregularities (mostly) due to poor screening of the nucleus by d and f electrons, and relativistic effects, tends to increase going down a group (or column or family). Thus, the most metallic elements (such as caesium and francium) are found at the bottom left of traditional periodic tables and the most nonmetallic elements (oxygen, fluorine, chlorine) at the top right. The combination of horizontal and vertical trends in metallic character explains the stair-shaped dividing line between metals and nonmetals found on some periodic tables, and the practice of sometimes categorizing several elements adjacent to that line, or elements adjacent to those elements, as metalloids.

Linking or bridging groups

From left to right across the four blocks of the long- or 32-column form of the periodic table are a series of linking or bridging groups of elements, located approximately between each block. These groups, like the metalloids, show properties in between, or that are a mixture of, groups to either side. Chemically, the group 3 elements, scandium, yttrium, lanthanum and actinium behave largely like the alkaline earth metals or, more generally, s block metals but have some of the physical properties of d block transition metals. Lutetium and lawrencium, at the end of the end of the f block, may constitute another linking or bridging group. Lutetium behaves chemically as a lanthanide but shows a mix of lanthanide and transition metal physical properties. Lawrencium, as an analogue of lutetium, would presumable display like characteristics. The coinage metals in group 11 (copper, silver, and gold) are chemically capable of acting as either transition metals or main group metals. The volatile group 12 metals, zinc, cadmium and mercury are sometimes regarded as linking the d block to the p block. Notionally they are d block elements but they have few transition metal properties and are more like their p block neighbors in group 13. The relatively inert noble gases, in group 18, bridge the most reactive groups of elements in the periodic table—the halogens in group 17 and the alkali metals in group 1.

History

First systemization attempts

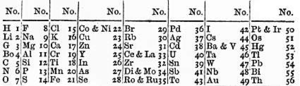

In 1789, Antoine Lavoisier published a list of 33 chemical elements, grouping them into gases, metals, nonmetals, and earths. Chemists spent the following century searching for a more precise classification scheme. In 1829, Johann Wolfgang Döbereiner observed that many of the elements could be grouped into triads based on their chemical properties. Lithium, sodium, and potassium, for example, were grouped together in a triad as soft, reactive metals. Döbereiner also observed that, when arranged by atomic weight, the second member of each triad was roughly the average of the first and the third; this became known as the Law of Triads. German chemist Leopold Gmelin worked with this system, and by 1843 he had identified ten triads, three groups of four, and one group of five. Jean-Baptiste Dumas published work in 1857 describing relationships between various groups of metals. Although various chemists were able to identify relationships between small groups of elements, they had yet to build one scheme that encompassed them all.

In 1857, German chemist August Kekulé observed that carbon often has four other atoms bonded to it. Methane, for example, has one carbon atom and four hydrogen atoms. This concept eventually became known as valency; different elements bond with different numbers of atoms.

In 1862, Alexandre-Emile Béguyer de Chancourtois, a French geologist, published an early form of periodic table, which he called the telluric helix or screw. He was the first person to notice the periodicity of the elements. With the elements arranged in a spiral on a cylinder by order of increasing atomic weight, de Chancourtois showed that elements with similar properties seemed to occur at regular intervals. His chart included some ions and compounds in addition to elements. His paper also used geological rather than chemical terms and did not include a diagram; as a result, it received little attention until the work of Dmitri Mendeleev.

In 1864, Julius Lothar Meyer, a German chemist, published a table with 44 elements arranged by valency. The table showed that elements with similar properties often shared the same valency. Concurrently, English chemist William Odling published an arrangement of 57 elements, ordered on the basis of their atomic weights. With some irregularities and gaps, he noticed what appeared to be a periodicity of atomic weights among the elements and that this accorded with "their usually received groupings". Odling alluded to the idea of a periodic law but did not pursue it. He subsequently proposed (in 1870) a valence-based classification of the elements.

English chemist John Newlands produced a series of papers from 1863 to 1866 noting that when the elements were listed in order of increasing atomic weight, similar physical and chemical properties recurred at intervals of eight; he likened such periodicity to the octavesof music. This so termed Law of Octaves was ridiculed by Newlands' contemporaries, and the Chemical Society refused to publish his work. Newlands was nonetheless able to draft a table of the elements and used it to predict the existence of missing elements, such as germanium. The Chemical Society only acknowledged the significance of his discoveries five years after they credited Mendeleev.

In 1867, Gustavus Hinrichs, a Danish born academic chemist based in America, published a spiral periodic system based on atomic spectra and weights, and chemical similarities. His work was regarded as idiosyncratic, ostentatious and labyrinthine and this may have militated against its recognition and acceptance.

Mendeleev's table

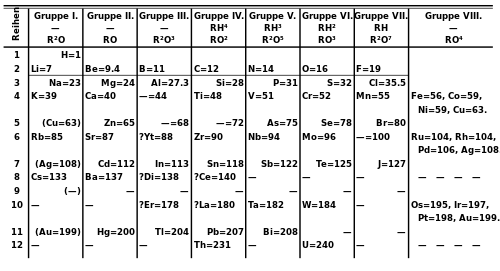

Russian chemistry professor Dmitri Mendeleev and German chemist Julius Lothar Meyer independently published their periodic tables in 1869 and 1870, respectively. Mendeleev's table was his first published version; that of Meyer was an expanded version of his (Meyer's) table of 1864. They both constructed their tables by listing the elements in rows or columns in order of atomic weight and starting a new row or column when the characteristics of the elements began to repeat.

The recognition and acceptance afforded to Mendeleev's table came from two decisions he made. The first was to leave gaps in the table when it seemed that the corresponding element had not yet been discovered. Mendeleev was not the first chemist to do so, but he was the first to be recognized as using the trends in his periodic table to predict the properties of those missing elements, such as gallium and germanium. The second decision was to occasionally ignore the order suggested by the atomic weights and switch adjacent elements, such as tellurium and iodine, to better classify them into chemical families.

Mendeleev published in 1869, using atomic weight to organize the elements, information determinable to fair precision in his time. Atomic weight worked well enough to allow Mendeleev to accurately predict the properties of missing elements.

Following the discovery, in 1911, by Ernest Rutherford of the atomic nucleus, it was proposed that the integer count of the nuclear charge is identical to the sequential place of each element in the periodic table. In 1913, Henry Moseleyusing X-ray spectroscopy confirmed this proposal experimentally. Moseley determined the value of the nuclear charge of each element, and showed that Mendeleev's ordering actually places the elements in sequential order by nuclear charge. Nuclear charge is identical to proton count, and determines the value of the atomic number (Z) of each element. Using atomic number gives a definitive, integer-based sequence for the elements. Moseley predicted, in 1913, that the only elements still missing between aluminium (Z=13) and gold (Z=79) were Z = 43, 61, 72, and 75, all of which were later discovered. The atomic number is the absolute definition of an element, and gives a factual basis for the ordering of the periodic table. The periodic table is used to predict the properties of new synthetic elements before they are produced and studied.

Second version and further development

In 1871, Mendeleev published his periodic table in a new form, with groups of similar elements arranged in columns rather than in rows, and those columns numbered I to VIII corresponding with the element's oxidation state. He also gave detailed predictions for the properties of elements he had earlier noted were missing, but should exist. These gaps were subsequently filled as chemists discovered additional naturally occurring elements. It is often stated that the last naturally occurring element to be discovered was francium (referred to by Mendeleev as eka-caesium) in 1939. Plutonium, produced synthetically in 1940, was identified in trace quantities as a naturally occurring element in 1971.

The popular periodic table layout, also known as the common or standard form (as shown at various other points in this article), is attributable to Horace Groves Deming. In 1923, Deming, an American chemist, published short (Mendeleev style) and medium (18-column) form periodic tables. Merck and Company prepared a handout form of Deming's 18-column medium table, in 1928, which was widely circulated in American schools. By the 1930s Deming's table was appearing in handbooks and encyclopaedias of chemistry. It was also distributed for many years by the Sargent-Welch Scientific Company.

With the development of modern quantum mechanical theories of electron configurations within atoms, it became apparent that each period (row) in the table corresponded to the filling of a quantum shell of electrons. Larger atoms have more electron sub-shells, so later tables have required progressively longer periods.

In 1945, Glenn Seaborg, an American scientist, made the suggestion that the actinide elements, like the lanthanides, were filling an f sub-level. Before this time the actinides were thought to be forming a fourth d-block row. Seaborg's colleagues advised him not to publish such a radical suggestion as it would most likely ruin his career. As Seaborg considered he did not then have a career to bring into disrepute, he published anyway. Seaborg's suggestion was found to be correct and he subsequently went on to win the 1951 Nobel Prizein chemistry for his work in synthesizing actinide elements.

Although minute quantities of some transuranic elements occur naturally,they were all first discovered in laboratories. Their production has expanded the periodic table significantly, the first of these being neptunium, synthesized in 1939. Because many of the transuranic elements are highly unstable and decay quickly, they are challenging to detect and characterize when produced. There have been controversies concerning the acceptance of competing discovery claims for some elements, requiring independent review to determine which party has priority, and hence naming rights. In 2010, a joint Russia–US collaboration at Dubna, Moscow Oblast, Russia, claimed to have synthesized six atoms of tennessine (element 117), making it the most recently claimed discovery. It, along with nihonium (element 113), moscovium (element 115), and oganesson (element 118), are the four most recently named elements, whose names all became official on 28 November 2016.

Different periodic tables

The long- or 32-column table

The modern periodic table is sometimes expanded into its long or 32-column form by reinstating the footnoted f-block elements into their natural position between the s- and d-blocks. Unlike the 18-column form this arrangement results in "no interruptions in the sequence of increasing atomic numbers". The relationship of the f-block to the other blocks of the periodic table also becomes easier to see. Jensen advocates a form of table with 32 columns on the grounds that the lanthanides and actinides are otherwise relegated in the minds of students as dull, unimportant elements that can be quarantined and ignored. Despite these advantages the 32-column form is generally avoided by editors on account of its undue rectangular ratio (compared to a book page ratio), and the familiarity of chemists with the modern form (as introduced by Seaborg).

Tables with different structures

Within 100 years of the appearance of Mendeleev's table in 1869 it has been estimated that around 700 different periodic table versions were published. As well as numerous rectangular variations, other periodic table formats have been shaped, for example, like a circle, cube, cylinder, building, spiral, lemniscate, octagonal prism, pyramid, sphere, or triangle. Such alternatives are often developed to highlight or emphasize chemical or physical properties of the elements that are not as apparent in traditional periodic tables.

A popular alternative structure is that of Theodor Benfey (1960). The elements are arranged in a continuous spiral, with hydrogen at the centre and the transition metals, lanthanides, and actinides occupying peninsulas.

Most periodic tables are two-dimensional; three-dimensional tables are known to as far back as at least 1862 (pre-dating Mendeleev's two-dimensional table of 1869). More recent examples include Courtines' Periodic Classification (1925), Wringley's Lamina System (1949),Giguère's Periodic helix (1965) and Dufour's Periodic Tree (1996). Going one further, Stowe's Physicist's Periodic Table (1989) has been described as being four-dimensional (having three spatial dimensions and one colour dimension).

The various forms of periodic tables can be thought of as lying on a chemistry–physics continuum. Towards the chemistry end of the continuum can be found, as an example, Rayner-Canham's "unruly" Inorganic Chemist's Periodic Table (2002), which emphasizes trends and patterns, and unusual chemical relationships and properties. Near the physics end of the continuum is Janet's Left-Step Periodic Table (1928). This has a structure that shows a closer connection to the order of electron-shell filling and, by association, quantum mechanics. A somewhat similar approach has been taken by Alper, albeit criticized by Eric Scerri as disregarding the need to display chemical and physical periodicity.Somewhere in the middle of the continuum is the ubiquitous common or standard form of periodic table. This is regarded as better expressing empirical trends in physical state, electrical and thermal conductivity, and oxidation numbers, and other properties easily inferred from traditional techniques of the chemical laboratory. Its popularity is thought to be a result of this layout having a good balance of features in terms of ease of construction and size, and its depiction of atomic order and periodic trends.

Left-step periodic table (by Charles Janet)

| f | f | f | f | f | f | f | f | f | f | f | f | f | f | d | d | d | d | d | d | d | d | d | d | p | p | p | p | p | p | s | s | |

| 1s | H | He | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| 2s | Li | Be | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| 2p 3s | B | C | N | O | F | Ne | Na | Mg | ||||||||||||||||||||||||

| 3p 4s | Al | Si | P | S | Cl | Ar | K | Ca | ||||||||||||||||||||||||

| 3d 4p 5s | Sc | Ti | V | Cr | Mn | Fe | Co | Ni | Cu | Zn | Ga | Ge | As | Se | Br | Kr | Rb | Sr | ||||||||||||||

| 4d 5p 6s | Y | Zr | Nb | Mo | Tc | Ru | Rh | Pd | Ag | Cd | In | Sn | Sb | Te | I | Xe | Cs | Ba | ||||||||||||||

| 4f 5d 6p 7s | La | Ce | Pr | Nd | Pm | Sm | Eu | Gd | Tb | Dy | Ho | Er | Tm | Yb | Lu | Hf | Ta | W | Re | Os | Ir | Pt | Au | Hg | Tl | Pb | Bi | Po | At | Rn | Fr | Ra |

| 5f 6d 7p 8s | Ac | Th | Pa | U | Np | Pu | Am | Cm | Bk | Cf | Es | Fm | Md | No | Lr | Rf | Db | Sg | Bh | Hs | Mt | Ds | Rg | Cn | Nh | Fl | Mc | Lv | Ts | Og | 119 | 120 |

| f-block | d-block | p-block | s-block | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

Open questions and controversies

Placement of hydrogen and helium

Simplemente siguiendo las configuraciones electrónicas, el hidrógeno (configuración electrónica 1s) y el helio (1s) deben colocarse en los grupos 1 y 2, por encima del litio (1s2s) y el berilio (1s2s). Aunque dicha colocación es común para el hidrógeno, rara vez se usa para helio fuera del contexto de las configuraciones de electrones: cuando los gases nobles (llamados entonces "gases inertes") se descubrieron por primera vez alrededor de 1900, se los conocía como "grupo 0", lo que no refleja reactividad química de estos elementos conocidos en ese punto, y helio se colocó en la parte superior de ese grupo, ya que compartía la inercia química extrema que se observa en todo el grupo. A medida que el grupo cambió su número formal, muchos autores continuaron asignando helio directamente por encima del neón, en el grupo 18; uno de los ejemplos de dicha colocación es la tabla IUPAC actual.

Las propiedades químicas del hidrógeno no son muy similares a las de los metales alcalinos, que ocupan el grupo 1. Sobre esta base, a veces se coloca en otro lugar. Una alternativa común está en la parte superior del grupo 17 dada la química estrictamente univalente y en gran parte no metálica del hidrógeno, y la química estrictamente univalente y no metálica del flúor (el elemento que de otro modo estaría en la parte superior del grupo 17). Algunas veces, para mostrar que el hidrógeno tiene propiedades que corresponden tanto a los metales alcalinos como a los halógenos, se muestra en la parte superior de las dos columnas al mismo tiempo. Otra sugerencia está por encima del carbono en el grupo 14: colocada de esa manera, encaja bien con las tendencias de aumentar los valores potenciales de ionización y los valores de afinidad electrónica, y no está muy lejos de la tendencia de la electronegatividad, aunque el hidrógeno no puede mostrar la tetravalencia característica de los elementos del grupo más pesado 14. Finalmente, el hidrógeno a veces se coloca por separado de cualquier grupo; esto se basa en que sus propiedades generales son diferentes de las de los elementos en cualquier otro grupo. El otro elemento del período 1, el helio, a veces se coloca por separado de cualquier grupo también. La propiedad que distingue al helio del resto de los gases nobles (aunque la extraordinaria inercia del helio es extremadamente similar a la del neón y el argón) es que en su capa de electrones cerrada, el helio tiene solo dos electrones en el orbital de electrones más externo, mientras que el resto de los gases nobles tienen ocho. esto se basa en que sus propiedades generales son diferentes de las de los elementos en cualquier otro grupo. El otro elemento del período 1, el helio, a veces se coloca por separado de cualquier grupo también. La propiedad que distingue al helio del resto de los gases nobles (aunque la extraordinaria inercia del helio es extremadamente similar a la del neón y el argón) es que en su capa de electrones cerrada, el helio tiene solo dos electrones en el orbital de electrones más externo, mientras que el resto de los gases nobles tienen ocho. esto se basa en que sus propiedades generales son diferentes de las de los elementos en cualquier otro grupo. El otro elemento del período 1, el helio, a veces se coloca por separado de cualquier grupo también. La propiedad que distingue al helio del resto de los gases nobles (aunque la extraordinaria inercia del helio es extremadamente similar a la del neón y el argón) es que en su capa de electrones cerrada, el helio tiene solo dos electrones en el orbital de electrones más externo, mientras que el resto de los gases nobles tienen ocho.

Grupo 3 y sus elementos en los períodos 6 y 7

Aunque el escandio y el itrio son siempre los primeros dos elementos en el grupo 3, la identidad de los siguientes dos elementos no está completamente resuelta. Son comúnmente el lantano y el actinio, y con menos frecuencia el lutecio y el lawrencio. Las dos variantes se originan a partir de las dificultades históricas al colocar los lantánidos en la tabla periódica y los argumentos en cuanto a dónde comienzan y terminan los elementos del bloque f . Se ha afirmado que tales argumentos son prueba de que "es un error dividir el sistema [periódico] en bloques muy delimitados". Una tercera variante muestra que las dos posiciones debajo del itrio están ocupadas por los lantánidos y los actínidos.

Se han hecho argumentos químicos y físicos en apoyo del lutecio y el lawrencio, pero la mayoría de los autores parecen no estar convencidos. La mayoría de los químicos que trabajan no saben que hay alguna controversia. En diciembre de 2015, se estableció un proyecto IUPAC para hacer una recomendación sobre el tema.

Lantano y actinio

La y Ac debajo de Y |

El lantano y el actinio se representan comúnmente como los miembros restantes del grupo 3. Se ha sugerido que este diseño se originó en la década de 1940, con la aparición de tablas periódicas que dependen de las configuraciones electrónicas de los elementos y la noción del electrón de diferenciación. Las configuraciones de cesio, bario y lantano son [Xe] 6s, [Xe] 6s y [Xe] 5d6s. El lantano tiene así un electrón de diferenciación 5d y esto lo establece "en el grupo 3 como el primer miembro del d-block para el período 6". En el grupo 3 se observa un conjunto consistente de configuraciones de electrones: escandio [Ar] 3d4s, itrio [Kr] 4d5s y lantano [Xe] 5d6s. Aún en el período 6, al iterbio se le asignó una configuración electrónica de [Xe] 4f5d6s y lutecio [Xe] 4f5d6s, " Más tarde, el trabajo espectroscópico descubrió que la configuración electrónica del yterbio era, de hecho, [Xe] 4f6s. Esto significaba que el iterbio y el lutecio, el último con [Xe] 4f5d6s, tenían 14 electrones f, lo que daba como resultado un electrón d "en lugar de un electrón f diferenciador" para el lutecio y lo convertía en un "candidato igualmente válido" con [Xe ] 5d6s lantano, para la posición de la tabla periódica del grupo 3 debajo del itrio. El lantano tiene la ventaja de la incumbencia ya que el electrón 5d aparece por primera vez en su estructura, mientras que aparece por tercera vez en el lutecio, habiendo hecho también una segunda segunda aparición en el gadolinio. Más tarde, el trabajo espectroscópico descubrió que la configuración electrónica del yterbio era, de hecho, [Xe] 4f6s. Esto significaba que el iterbio y el lutecio, el último con [Xe] 4f5d6s, tenían 14 electrones f, lo que daba como resultado un electrón d "en lugar de un electrón f diferenciador" para el lutecio y lo convertía en un "candidato igualmente válido" con [Xe ] 5d6s lantano, para la posición de la tabla periódica del grupo 3 debajo del itrio. El lantano tiene la ventaja de la incumbencia ya que el electrón 5d aparece por primera vez en su estructura, mientras que aparece por tercera vez en el lutecio, habiendo hecho también una segunda segunda aparición en el gadolinio.

In terms of chemical behaviour, and trends going down group 3 for properties such as melting point, electronegativity and ionic radius, scandium, yttrium, lanthanum and actinium are similar to their group 1–2 counterparts. In this variant, the number of f electrons in the most common (trivalent) ions of the f-block elements consistently matches their position in the f-block. For example, the f-electron counts for the trivalent ions of the first three f-block elements are Ce 1, Pr 2 and Nd 3.

Lutetium and lawrencium

Lu and Lr below Y |

In other tables, lutetium and lawrencium are the remaining group 3 members. Early techniques for chemically separating scandium, yttrium and lutetium relied on the fact that these elements occurred together in the so-called "yttrium group" whereas La and Ac occurred together in the "cerium group". Accordingly, lutetium rather than lanthanum was assigned to group 3 by some chemists in the 1920s and 30s. Several physicists in the 1950s and '60s favoured lutetium, in light of a comparison of several of its physical properties with those of lanthanum. This arrangement, in which lanthanum is the first member of the f-block, is disputed by some authors since lanthanum lacks any f-electrons. It has been argued that this is not valid concern given other periodic table anomalies—thorium, for example, has no f-electrons yet is part of the f-block. As for lawrencium, its gas phase atomic electron configuration was confirmed in 2015 as [Rn]5f7s7p. Such a configuration represents another periodic table anomaly, regardless of whether lawrencium is located in the f-block or the d-block, as the only potentially applicable p-block position has been reserved for nihonium with its predicted configuration of [Rn]5f6d7s7p.

Chemically, scandium, yttrium and lutetium (and presumably lawrencium) behave like trivalent versions of the group 1–2 metals. On the other hand, trends going down the group for properties such as melting point, electronegativity and ionic radius, are similar to those found among their group 4–8 counterparts. In this variant, the number of f electrons in the gaseous forms of the f-block atoms usually matches their position in the f-block. For example, the f-electron counts for the first five f-block elements are La 0, Ce 1, Pr 3, Nd 4 and Pm 5.

Lanthanides and actinides

Markers below Y |

A few authors position all thirty lanthanides and actinides in the two positions below yttrium (usually via footnote markers). This variant emphasizes similarities in the chemistry of the 15 lanthanide elements (La–Lu), possibly at the expense of ambiguity as to which elements occupy the two group 3 positions below yttrium, and a 15-column wide f block (there can only be 14 elements in any row of the f block).

Groups included in the transition metals

The definition of a transition metal, as given by IUPAC, is an element whose atom has an incomplete d sub-shell, or which can give rise to cations with an incomplete d sub-shell. By this definition all of the elements in groups 3–11 are transition metals. The IUPAC definition therefore excludes group 12, comprising zinc, cadmium and mercury, from the transition metals category.

Some chemists treat the categories "d-block elements" and "transition metals" interchangeably, thereby including groups 3–12 among the transition metals. In this instance the group 12 elements are treated as a special case of transition metal in which the d electrons are not ordinarily involved in chemical bonding. The 2007 report of mercury(IV) fluoride (HgF4), a compound in which mercury would use its d electrons for bonding, has prompted some commentators to suggest that mercury can be regarded as a transition metal. Other commentators, such as Jensen, have argued that the formation of a compound like HgF4 can occur only under highly abnormal conditions; indeed, its existence is currently disputed. As such, mercury could not be regarded as a transition metal by any reasonable interpretation of the ordinary meaning of the term.

Still other chemists further exclude the group 3 elements from the definition of a transition metal. They do so on the basis that the group 3 elements do not form any ions having a partially occupied d shell and do not therefore exhibit any properties characteristic of transition metal chemistry. In this case, only groups 4–11 are regarded as transition metals. Though the group 3 elements show few of the characteristic chemical properties of the transition metals, they do show some of their characteristic physical properties (on account of the presence in each atom of a single d electron).

Elementos con propiedades químicas desconocidas

Aunque se han descubierto todos los elementos hasta oganesson, de los elementos anteriores de hassium (elemento 108), solo copernicium (elemento 112), nihonium (elemento 113) y flerovium (elemento 114) tienen propiedades químicas conocidas, y solo para copernicium existe suficiente evidencia para una categorización concluyente en la actualidad. Los otros elementos pueden comportarse de manera diferente de lo que se predeciría mediante la extrapolación, debido a los efectos relativistas; por ejemplo, se ha predicho que el flerovium exhibirá algunas propiedades similares a los gases nobles, a pesar de que actualmente se encuentra en el grupo de carbono. La evidencia experimental actual aún deja abierta la pregunta de si el flerovium se comporta más como un metal o un gas noble.

Otras extensiones de tabla periódica

No está claro si los elementos nuevos continuarán con el patrón de la tabla periódica actual como período 8, o si requieren más adaptaciones o ajustes. Seaborg esperaba que el octavo período siguiera exactamente el patrón establecido previamente, de modo que incluiría un s-block de dos elementos para los elementos 119 y 120, un nuevo bloque g para los siguientes 18 elementos y 30 elementos adicionales que continúan la corriente f -, d-, y p-blocks, que culminan en el elemento 168, el próximo gas noble. Más recientemente, físicos como Pekka Pyykkö han teorizado que estos elementos adicionales no siguen la regla de Madelung, que predice cómo se llenan los depósitos de electrones y, por lo tanto, afecta la apariencia de la tabla periódica actual. Actualmente hay varios modelos teóricos en competencia para la colocación de los elementos de número atómico menor o igual a 172.

Elemento con el número atómico más alto posible

La cantidad de elementos posibles no se conoce. Una sugerencia muy temprana hecha por Elliot Adams en 1911, y basada en la disposición de elementos en cada fila de la tabla periódica horizontal, era que los elementos de peso atómico eran mayores que alrededor de 256 (lo que equivale a entre los elementos 99 y 100 en términos modernos ) no existió. Una estimación más alta-más reciente es que la tabla periódica puede finalizar poco después de la isla de estabilidad, que se espera que se centre en el elemento 126, ya que la extensión de las tablas periódica y de núclidos está restringida por líneas de goteo de protones y neutrones. Otras predicciones de un final de la tabla periódica incluyen en el elemento 128 de John Emsley, en el elemento 137 de Richard Feynman, y en el elemento 155 de Albert Khazan.

- Modelo de Bohr

El modelo de Bohr presenta dificultad para los átomos con un número atómico mayor que 137, ya que cualquier elemento con un número atómico mayor a 137 requeriría que los electrones viajaran más rápido que c , la velocidad de la luz. Por lo tanto, el modelo de Bohr no relativista es inexacto cuando se aplica a dicho elemento.

- Ecuación relativista de Dirac

La ecuación relativista de Dirac tiene problemas para los elementos con más de 137 protones. Para tales elementos, la función de onda del estado fundamental de Dirac es oscilatoria en lugar de limitada, y no hay espacio entre los espectros de energía positiva y negativa, como en la paradoja de Klein. Cálculos más precisos que tengan en cuenta los efectos del tamaño finito del núcleo indican que la energía de enlace primero excede el límite de los elementos con más de 173 protones. Para elementos más pesados, si el orbital más interno (1s) no está lleno, el campo eléctrico del núcleo extraerá un electrón del vacío, lo que resultará en la emisión espontánea de un positrón. Esto no ocurre si el orbital más interno está lleno, por lo que el elemento 173 no es necesariamente el final de la tabla periódica.

Forma óptima

Las diferentes formas de tabla periódica han provocado la pregunta de si existe una forma óptima o definitiva de tabla periódica. Se cree que la respuesta a esta pregunta depende de si la periodicidad química que se observa entre los elementos tiene una verdad subyacente, efectivamente conectada al universo, o si dicha periodicidad es producto de la interpretación humana subjetiva, depende de la circunstancias, creencias y predilecciones de los observadores humanos. Una base objetiva para la periodicidad química resolvería las preguntas sobre la ubicación del hidrógeno y el helio, y la composición del grupo 3. Tal verdad subyacente, si existe, se cree que todavía no se ha descubierto. En su ausencia, las muchas formas diferentes de tabla periódica se pueden considerar como variaciones sobre el tema de la periodicidad química,

Obtenido de: https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Periodic_table