Historia de la medicina

Definición

La historia de la medicina muestra cómo las sociedades han cambiado en su enfoque de enfermedad y enfermedad desde la antigüedad hasta el presente.

Las primeras tradiciones médicas incluyen las de Babilonia, China, Egipto e India. Los griegos introdujeron los conceptos de diagnóstico médico, pronóstico y ética médica avanzada. El juramento hipocrático fue escrito en la antigua Grecia en el siglo V a. EC, y es una inspiración directa para los juramentos que los médicos juran al ingresar a la profesión hoy en día. En la edad medieval, las prácticas quirúrgicas heredadas de los maestros antiguos mejoraron y luego se sistematizaron en The Practice of Surgery de Rogerius. . Las universidades comenzaron la capacitación sistemática de médicos alrededor de los años 1220 en Italia. Durante el Renacimiento, la comprensión de la anatomía mejoró, y el microscopio fue inventado. La teoría de los gérmenes de la enfermedad en el siglo XIX dio lugar a la curación de muchas enfermedades infecciosas. Los médicos militares avanzaron los métodos de tratamiento y cirugía de trauma. Las medidas de salud pública se desarrollaron especialmente en el siglo XIX, ya que el rápido crecimiento de las ciudades requería medidas sanitarias sistemáticas. Los centros de investigación avanzada se abrieron a principios del siglo XX, a menudo conectados con los principales hospitales. A mediados del siglo XX, se caracterizó por nuevos tratamientos biológicos, como los antibióticos. Estos avances, junto con los desarrollos en química, genética y radiografía llevaron a la medicina moderna. La medicina fue muy profesionalizada en el siglo 20,

Medicina prehistórica

Aunque no existe un registro para establecer cuándo las plantas se utilizaron por primera vez con fines medicinales (herboristería), el uso de plantas como agentes curativos, así como las arcillas y los suelos es antiguo. Con el tiempo, a través de la emulación del comportamiento de la fauna, se desarrolló y pasó una base de conocimiento medicinal entre generaciones. Como cultura tribal, las castas específicas especializadas, chamanes y boticarios cumplían el papel de sanador. La primera odontología conocida data del año 7000 aC en Baluchistán, donde los dentistas neolíticos utilizaban taladros con punta de sílex y cuerdas de arco. La primera operación de trepanación conocida se llevó a cabo alrededor de 5000 aC en Ensisheim, Francia. Una posible amputación se llevó a cabo c 4.900 aC en Buthiers-Bulancourt, Francia.

Primeras civilizaciones

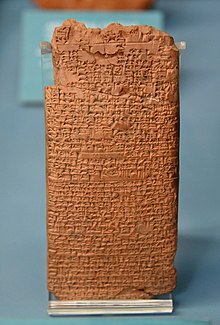

Mesopotamia

Los antiguos mesopotámicos no tenían distinción entre "ciencia racional" y magia. Cuando una persona se enferma, los médicos prescriben tanto fórmulas mágicas para recitar como tratamientos medicinales. Las primeras prescripciones médicas aparecen en sumerio durante la Tercera Dinastía de Ur ( circa 2112 aC - c. 2004 aC). Los textos babilónicos más antiguos sobre medicina datan del período del Antiguo Babilonia en la primera mitad del segundo milenio a. El texto médico más extenso de Babilonia, sin embargo, es el Manual de Diagnóstico escrito por el ummânūo erudito principal, Esagil-kin-apli de Borsippa, durante el reinado del rey de Babilonia Adad-apla-iddina (1069-1046 aC). Junto con los egipcios, los babilonios introdujeron la práctica del diagnóstico, el pronóstico, el examen físico y los remedios. Además, el Manual de diagnóstico introdujo los métodos de terapia y causa. El texto contiene una lista de síntomas médicos y, a menudo, observaciones empíricas detalladas junto con las reglas lógicas que se usan para combinar los síntomas observados en el cuerpo de un paciente con su diagnóstico y pronóstico. El manual de diagnóstico se basó en un conjunto lógico de axiomas y suposiciones, incluida la visión moderna de que a través del examen e inspección de los síntomas de un paciente, es posible determinar la enfermedad del paciente, su causa y desarrollo futuro, y las posibilidades de recuperación del paciente . Los síntomas y enfermedades de un paciente fueron tratados a través de medios terapéuticos, como vendas, hierbas y cremas.

En las culturas semitas orientales, la principal autoridad medicinal era una especie de sanador exorcista conocido como āšipu . La profesión generalmente se transmitía de padre a hijo y era muy apreciada. El recurso menos frecuente fue otro tipo de sanador conocido como asu , que se corresponde más estrechamente con un médico moderno y trató los síntomas físicos utilizando principalmente remedios caseros compuestos por diversas hierbas, productos animales y minerales, así como pociones, enemas y ungüentos o cataplasmas Estos médicos, que podían ser hombres o mujeres, también vestían heridas, colocaban extremidades y realizaban cirugías simples. Los antiguos mesopotámicos también practicaron la profilaxis y tomaron medidas para prevenir la propagación de la enfermedad.

Las enfermedades mentales eran bien conocidas en la antigua Mesopotamia, donde se creía que las enfermedades y los trastornos mentales eran causados por deidades específicas. Debido a que las manos simbolizaban el control sobre una persona, las enfermedades mentales eran conocidas como "manos" de ciertas deidades. Una enfermedad psicológica era conocida como Qāt Ištar, que significa "Mano de Ishtar". Otros eran conocidos como "Mano de Shamash", "Mano del Fantasma" y "Mano del Dios". Las descripciones de estas enfermedades, sin embargo, son tan vagas que, por lo general, es imposible determinar a qué enfermedades corresponden en la terminología moderna. Los médicos de Mesopotamia mantuvieron un registro detallado de las alucinaciones de sus pacientes y les asignaron significados espirituales. Se pronosticaba que moriría un paciente que alucinó que estaba viendo un perro; mientras que, si viera una gacela, se recuperaría. La familia real de Elam era notoria porque sus miembros frecuentemente sufrían de demencia. La disfunción eréctil fue reconocida como arraigada en problemas psicológicos.

Egipto

El antiguo Egipto desarrolló una gran, variada y fructífera tradición médica. Herodoto describió a los egipcios como "el hombre más sano de todos, junto con los libios", debido al clima seco y al notable sistema de salud pública que poseían. Según él, "la práctica de la medicina es tan especial entre ellos que cada médico es un sanador de una enfermedad y nada más". Aunque la medicina egipcia, en gran medida, se ocupó de lo sobrenatural, finalmente desarrolló un uso práctico en los campos de la anatomía, la salud pública y el diagnóstico clínico.

Medical information in the Edwin Smith Papyrus may date to a time as early as 3000 BC. Imhotep in the 3rd dynasty is sometimes credited with being the founder of ancient Egyptian medicine and with being the original author of the Edwin Smith Papyrus, detailing cures, ailments and anatomical observations. The Edwin Smith Papyrus is regarded as a copy of several earlier works and was written c. 1600 BC. It is an ancient textbook on surgery almost completely devoid of magical thinking and describes in exquisite detail the examination, diagnosis, treatment, and prognosis of numerous ailments.

The Kahun Gynaecological Papyrus treats women's complaints, including problems with conception. Thirty four cases detailing diagnosis and treatment survive, some of them fragmentarily. Dating to 1800 BCE, it is the oldest surviving medical text of any kind.

Medical institutions, referred to as Houses of Life are known to have been established in ancient Egypt as early as 2200 BC.

The earliest known physician is also credited to ancient Egypt: Hesy-Ra, "Chief of Dentists and Physicians" for King Djoser in the 27th century BCE. Also, the earliest known woman physician, Peseshet, practiced in Ancient Egypt at the time of the 4th dynasty. Her title was "Lady Overseer of the Lady Physicians." In addition to her supervisory role, Peseshet trained midwives at an ancient Egyptian medical school in Sais.

India

The Atharvaveda, a sacred text of Hinduism dating from the Early Iron Age, is one of the first Indian text dealing with medicine. The Atharvaveda also contain prescriptions of herbs for various ailments. The use of herbs to treat ailments would later form a large part of Ayurveda.

Ayurveda, meaning the "complete knowledge for long life" is another medical system of India. Its two most famous texts belong to the schools of Charaka and Sushruta. The earliest foundations of Ayurveda were built on a synthesis of traditional herbal practices together with a massive addition of theoretical conceptualizations, new nosologies and new therapies dating from about 600 BCE onwards, and coming out of the communities of thinkers who included the Buddha and others.

According to the compendium of Charaka, the Charakasamhitā, health and disease are not predetermined and life may be prolonged by human effort. The compendium of Suśruta, the Suśrutasamhitā defines the purpose of medicine to cure the diseases of the sick, protect the healthy, and to prolong life. Both these ancient compendia include details of the examination, diagnosis, treatment, and prognosis of numerous ailments. The Suśrutasamhitā is notable for describing procedures on various forms of surgery, including rhinoplasty, the repair of torn ear lobes, perineal lithotomy, cataract surgery, and several other excisions and other surgical procedures. Most remarkable is Sushruta's penchant for scientific classification: His medical treatise consists of 184 chapters, 1,120 conditions are listed, including injuries and illnesses relating to aging and mental illness.

Los clásicos ayurvédicos mencionan ocho ramas de la medicina: kāyācikitsā (medicina interna), śalyacikitsā (cirugía que incluye la anatomía), śālākyacikitsā (enfermedades del ojo, oído, nariz y garganta), kaumārabhṛtya (pediatría con obstetricia y ginecología), bhūtavidyā (espíritu y medicina psiquiátrica) ), agada tantra (toxicología con tratamientos de picaduras y mordeduras), rasāyana (ciencia del rejuvenecimiento) y vājīkaraṇa (afrodisíaco y fertilidad). Además de aprender esto, se esperaba que el estudiante de Āyurveda supiera diez artes que eran indispensables en la preparación y aplicación de sus medicamentos: destilación, habilidades operativas, cocina, horticultura, metalurgia, fabricación de azúcar, farmacia, análisis y separación de minerales, compuestos de metales y preparación de álcalis. La enseñanza de diversas materias se realizó durante la instrucción de temas clínicos relevantes. Por ejemplo, la enseñanza de la anatomía era parte de la enseñanza de la cirugía, la embriología era parte de la formación en pediatría y obstetricia, y el conocimiento de la fisiología y la patología se entrelazó en la enseñanza de todas las disciplinas clínicas. La duración normal de la capacitación del estudiante parece haber sido de siete años. Pero el médico debía continuar aprendiendo.

Como una forma alternativa de medicina en la India, la medicina Unani obtuvo raíces profundas y el patrocinio real durante la época medieval. Progresó durante el sultanato indio y los períodos mughal. La medicina de Unani está muy cerca de Ayurveda. Ambos se basan en la teoría de la presencia de los elementos (en Unani, se consideran fuego, agua, tierra y aire) en el cuerpo humano. Según los seguidores de la medicina Unani, estos elementos están presentes en diferentes fluidos y su equilibrio conduce a la salud y su desequilibrio conduce a la enfermedad.

En el siglo XVIII, la sabiduría médica sánscrita todavía dominaba. Los gobernantes musulmanes construyeron grandes hospitales en 1595 en Hyderabad, y en Delhi en 1719, y se escribieron numerosos comentarios sobre textos antiguos.

China

China también desarrolló un gran cuerpo de medicina tradicional. Gran parte de la filosofía de la medicina tradicional china deriva de las observaciones empíricas de la enfermedad y la enfermedad por parte de los médicos taoístas y refleja la creencia clásica china de que las experiencias humanas individuales expresan principios causales efectivos en el medio ambiente en todas las escalas. Estos principios causales, ya sean materiales, esenciales o místicos, se correlacionan como la expresión del orden natural del universo.

El texto fundamental de la medicina china es el Huangdi neijing (o el canon interno del emperador amarillo ), escrito desde el siglo V hasta el siglo III a. Cerca del final del siglo II d. C., durante la dinastía Han, Zhang Zhongjing, escribió un Tratado sobre el daño por frío , que contiene la referencia más antigua conocida del Neijing Suwen . El practicante de la Dinastía Jin y defensor de la acupuntura y la moxibustión, Huangfu Mi (215-282), también cita al Emperador Amarillo en su Jiayi jing , c. 265. Durante la dinastía Tang, el Suwen fue ampliado y revisado, y ahora es la mejor representación existente de las raíces fundamentales de la medicina tradicional china. La medicina tradicional china que se basa en el uso de la medicina herbal, la acupuntura, el masaje y otras formas de terapia se ha practicado en China durante miles de años.

En el siglo XVIII, durante la dinastía Qing, hubo una proliferación de libros populares y enciclopedias más avanzadas sobre medicina tradicional. Los misioneros jesuitas introdujeron la ciencia y la medicina occidental en la corte real, los médicos chinos los ignoraron.

Finalmente, en el siglo XIX, la medicina occidental fue introducida a nivel local por misioneros médicos cristianos de la Sociedad Misionera de Londres (Gran Bretaña), la Iglesia Metodista (Gran Bretaña) y la Iglesia Presbiteriana (EE. UU.). Benjamin Hobson (1816-1873) en 1839, estableció una exitosa Clínica Wai Ai en Guangzhou, China. El Colegio de Medicina de Hong Kong para chinos fue fundado en 1887 por la Sociedad Misionera de Londres, con su primer graduado (en 1892) siendo Sun Yat-sen, quien más tarde dirigió la Revolución China (1911). El Colegio de Medicina de Hong Kong para chinos fue el precursor de la Facultad de Medicina de la Universidad de Hong Kong, que comenzó en 1911.

Debido a la costumbre social de que los hombres y las mujeres no deberían estar cerca unos de otros, las mujeres de China eran reacias a ser tratadas por médicos varones. Los misioneros enviaron doctoras como la Dra. Mary Hannah Fulton (1854-1927). Con el apoyo de la Junta de Misiones Extranjeras de la Iglesia Presbiteriana (EE. UU.), En 1902 fundó la primera facultad de medicina para mujeres en China, la Facultad de Medicina Hackett para Mujeres, en Guangzhou.

Grecia y el Imperio Romano

Around 800 BCE Homer in The Iliad gives descriptions of wound treatment by the two sons of Asklepios, the admirable physicians Podaleirius and Machaon and one acting doctor, Patroclus. Because Machaon is wounded and Podaleirius is in combat Eurypylus asks Patroclus to cut out this arrow from my thigh, wash off the blood with warm water and spread soothing ointment on the wound. Asklepios like Imhotep becomes god of healing over time.

Temples dedicated to the healer-god Asclepius, known as Asclepieia (Ancient Greek: Ἀσκληπιεῖα, sing. Ἀσκληπιεῖον, 'Asclepieion), functioned as centers of medical advice, prognosis, and healing. At these shrines, patients would enter a dream-like state of induced sleep known as enkoimesis (ἐγκοίμησις) not unlike anesthesia, in which they either received guidance from the deity in a dream or were cured by surgery. Asclepeia provided carefully controlled spaces conducive to healing and fulfilled several of the requirements of institutions created for healing. In the Asclepeion of Epidaurus, three large marble boards dated to 350 BCE preserve the names, case histories, complaints, and cures of about 70 patients who came to the temple with a problem and shed it there. Some of the surgical cures listed, such as the opening of an abdominal abscess or the removal of traumatic foreign material, are realistic enough to have taken place, but with the patient in a state of enkoimesis induced with the help of soporific substances such as opium. Alcmaeon of Croton wrote on medicine between 500 and 450 BCE. He argued that channels linked the sensory organs to the brain, and it is possible that he discovered one type of channel, the optic nerves, by dissection.

Hippocrates

A towering figure in the history of medicine was the physician Hippocrates of Kos (c. 460 – c. 370 BCE), considered the "father of modern medicine." The Hippocratic Corpus is a collection of around seventy early medical works from ancient Greece strongly associated with Hippocrates and his students. Most famously, Hippocrates invented the Hippocratic Oath for physicians. Until today physicians swear an oath of office, which includes aspects found already in the Hippocratic Oath, (such as not to give a lethal dose of medicines, even if requested by the patient).

Hippocrates and his followers were first to describe many diseases and medical conditions. He is given credit for the first description of clubbing of the fingers, an important diagnostic sign in chronic suppurative lung disease, lung cancer and cyanotic heart disease. For this reason, clubbed fingers are sometimes referred to as "Hippocratic fingers". Hippocrates was also the first physician to describe the Hippocratic face in Prognosis. Shakespeare famously alludes to this description when writing of Falstaff's death in Act II, Scene iii. of Henry V.

Hippocrates began to categorize illnesses as acute, chronic, endemic and epidemic, and use terms such as, "exacerbation, relapse, resolution, crisis, paroxysm, peak, and convalescence."

Another of Hippocrates's major contributions may be found in his descriptions of the symptomatology, physical findings, surgical treatment and prognosis of thoracic empyema, i.e. suppuration of the lining of the chest cavity. His teachings remain relevant to present-day students of pulmonary medicine and surgery. Hippocrates was the first documented person to practise cardiothoracic surgery, and his findings are still valid.

Some of the techniques and theories developed by Hippocrates are now put into practice by the fields of Environmental and Integrative Medicine. These include recognizing the importance of taking a complete history which includes environmental exposures as well as foods eaten by the patient which might play a role in his or her illness.

Herophilus and Erasistratus

Two great Alexandrians laid the foundations for the scientific study of anatomy and physiology, Herophilus of Chalcedon and Erasistratus of Ceos. Other Alexandrian surgeons gave us ligature (hemostasis), lithotomy, hernia operations, ophthalmic surgery, plastic surgery, methods of reduction of dislocations and fractures, tracheotomy, and mandrake as an anaesthetic. Some of what we know of them comes from Celsus and Galen of Pergamum.

Herophilus of Chalcedon, working at the medical school of Alexandria placed intelligence in the brain, and connected the nervous system to motion and sensation. Herophilus also distinguished between veins and arteries, noting that the latter pulse while the former do not. He and his contemporary, Erasistratus of Chios, researched the role of veins and nerves, mapping their courses across the body. Erasistratus connected the increased complexity of the surface of the human brain compared to other animals to its superior intelligence. He sometimes employed experiments to further his research, at one time repeatedly weighing a caged bird, and noting its weight loss between feeding times. In Erasistratus' physiology, air enters the body, is then drawn by the lungs into the heart, where it is transformed into vital spirit, and is then pumped by the arteries throughout the body. Some of this vital spirit reaches the brain, where it is transformed into animal spirit, which is then distributed by the nerves.

Galen

The Greek Galen (c. 129–216 CE) was one of the greatest physicians of the ancient world, studying and traveling widely in ancient Rome. He dissected animals to learn about the body, and performed many audacious operations—including brain and eye surgeries— that were not tried again for almost two millennia. In Ars medica ("Arts of Medicine"), he explained mental properties in terms of specific mixtures of the bodily parts.

Galen's medical works were regarded as authoritative until well into the Middle Ages. Galen left a physiological model of the human body that became the mainstay of the medieval physician's university anatomy curriculum, but it suffered greatly from stasis and intellectual stagnation because some of Galen's ideas were incorrect; he did not dissect a human body. Greek and Roman taboos had meant that dissection was usually banned in ancient times, but in the Middle Ages it changed.

In 1523 Galen's On the Natural Faculties was published in London. In the 1530s Belgian anatomist and physician Andreas Vesalius launched a project to translate many of Galen's Greek texts into Latin. Vesalius's most famous work, De humani corporis fabrica was greatly influenced by Galenic writing and form.

Roman contributions

The Romans invented numerous surgical instruments, including the first instruments unique to women, as well as the surgical uses of forceps, scalpels, cautery, cross-bladed scissors, the surgical needle, the sound, and speculas. Romans also performed cataract surgery.

The Roman army physician Dioscorides (c. 40–90 CE), was a Greek botanist and pharmacologist. He wrote the encyclopedia De Materia Medica describing over 600 herbal cures, forming an influential pharmacopoeia which was used extensively for the following 1,500 years.

The Middle Ages, 400 to 1400

Byzantine Empire and Sassanid Empire

Byzantine medicine encompasses the common medical practices of the Byzantine Empire from about 400 AD to 1453 AD. Byzantine medicine was notable for building upon the knowledge base developed by its Greco-Roman predecessors. In preserving medical practices from antiquity, Byzantine medicine influenced Islamic medicine as well as fostering the Western rebirth of medicine during the Renaissance.

Byzantine physicians often compiled and standardized medical knowledge into textbooks. Their records tended to include both diagnostic explanations and technical drawings. The Medical Compendium in Seven Books, written by the leading physician Paul of Aegina, survived as a particularly thorough source of medical knowledge. This compendium, written in the late seventh century, remained in use as a standard textbook for the following 800 years.

La Antigüedad tardía marcó el comienzo de una revolución en la ciencia médica, y los registros históricos a menudo mencionan hospitales civiles (aunque la medicina del campo de batalla y el triage durante la guerra se registraron mucho antes de la Roma Imperial). Constantinopla se destacó como un centro de la medicina durante la Edad Media, que fue ayudado por su ubicación en la encrucijada, la riqueza y el conocimiento acumulado. contenido copiado de la medicina bizantina; ver el historial de esa página para la atribución

El primer ejemplo conocido de separación de gemelos unidos ocurrió en el Imperio bizantino en el siglo X. El siguiente ejemplo de separación de gemelos unidos se registrará por primera vez muchos siglos más tarde en Alemania en 1689.

Los vecinos del imperio bizantino, el imperio persa de Sassanid, también hicieron sus contribuciones notables principalmente con el establecimiento de la Academia de Gondeshapur, que era "el centro médico más importante del mundo antiguo durante los 6tos y 7tos siglos". Además, Cyril Elgood, médico británico e historiador de la medicina en Persia, comentó que gracias a los centros médicos como la Academia de Gondeshapur, "en gran medida, el crédito para todo el sistema hospitalario debe darse a Persia".

Mundo islámico

La civilización islámica se elevó a la primacía en la ciencia médica ya que sus médicos contribuyeron significativamente al campo de la medicina, incluyendo la anatomía, la oftalmología, la farmacología, la farmacia, la fisiología, la cirugía y las ciencias farmacéuticas. Los árabes fueron influenciados por antiguas prácticas médicas indias, persas, griegas, romanas y bizantinas, y los ayudaron a desarrollarse aún más. Galeno e Hipócrates eran autoridades preeminentes. La traducción de 129 de las obras de Galeno al árabe por el cristiano nestoriano Hunayn ibn Ishaq y sus asistentes, y en particular la insistencia de Galeno en un enfoque racional y sistemático de la medicina, estableció la plantilla para la medicina islámica, que se extendió rápidamente por todo el Imperio árabe. Mientras que Europa estaba en su Edad Media, el Islam se expandió en el oeste de Asia y disfrutó de una edad de oro. Sus médicos más famosos incluyeron a Muhammad ibn Zakariya al-Razi y al sabio Ibn Sina, quien escribió más de 40 obras sobre salud, medicina y bienestar. Tomando pistas de Grecia y Roma, los eruditos islámicos mantuvieron vivos el arte y la ciencia de la medicina y avanzaron.

Europa

Después de 400 dC, el estudio y la práctica de la medicina en el Imperio Romano de Occidente entraron en un profundo declive. Se proporcionaron servicios médicos, especialmente para los pobres, en los miles de hospitales monásticos que surgieron en toda Europa, pero la atención fue rudimentaria y principalmente paliativa. La mayoría de los escritos de Galeno e Hipócrates se perdieron en Occidente, y los resúmenes y compendios de San Isidro de Sevilla fueron el canal principal para transmitir las ideas médicas griegas. El renacimiento carolingio trajo un mayor contacto con Bizancio y una mayor conciencia de la medicina antigua, pero solo con el renacimiento del siglo XII y las nuevas traducciones provenientes de fuentes musulmanas y judías en España, y la inundación de recursos del siglo XV después de la caída de Constantinopla. West recupera por completo su conocimiento de la antigüedad clásica.

Los tabúes griegos y romanos habían significado que la disección fuera prohibida en la antigüedad, pero en la Edad Media cambió: los profesores de medicina y los estudiantes de Bolonia comenzaron a abrir cuerpos humanos, y Mondino de Luzzi (alrededor de 1275-1326) produjo los primeros libro de texto de anatomía basado en disección humana.

Wallis identifica una jerarquía de prestigio con los médicos universitarios en la parte superior, seguidos por cirujanos expertos; cirujanos entrenados en el oficio; cirujanos barberos; especialistas itinerantes como dentistas y oculistas; empiricos; y parteras

Escuelas

Las primeras escuelas de medicina se abrieron en el siglo IX, especialmente la Schola Medica Salernitana en Salerno, en el sur de Italia. Las influencias cosmopolitas de las fuentes griega, latina, árabe y hebrea le dieron una reputación internacional como la Ciudad Hipocrática. Los estudiantes de familias adineradas vinieron por tres años de estudios preliminares y cinco de estudios médicos. La medicina, siguiendo las leyes de Federico II, que fundó en 1224 la Universidad, mejoró la Schola Salernitana, en el período comprendido entre 1200 y 1400, tuvo en Sicilia (la llamada Edad Media siciliana) un desarrollo particular tanto para crear una verdadera escuela de medicina judía.

As a result of which, after a legal examination, was conferred to a Jewish Sicilian woman, Virdimura, wife of another physician Pasquale of Catania, the hystorical record of before woman officially trained to exercise of the medical profession.

By the thirteenth century, the medical school at Montpellier began to eclipse the Salernitan school. In the 12th century, universities were founded in Italy, France, and England, which soon developed schools of medicine. The University of Montpellier in France and Italy's University of Padua and University of Bologna were leading schools. Nearly all the learning was from lectures and readings in Hippocrates, Galen, Avicenna, and Aristotle.

Humours

The underlying principle of most medieval medicine was Galen's theory of humours. This was derived from the ancient medical works, and dominated all western medicine until the 19th century. The theory stated that within every individual there were four humours, or principal fluids – black bile, yellow bile, phlegm, and blood, these were produced by various organs in the body, and they had to be in balance for a person to remain healthy. Too much phlegm in the body, for example, caused lung problems; and the body tried to cough up the phlegm to restore a balance. The balance of humours in humans could be achieved by diet, medicines, and by blood-letting, using leeches. The four humours were also associated with the four seasons, black bile-autumn, yellow bile-summer, phlegm-winter and blood-spring.

Healing included both physical and spiritual therapeutics, such as the right herbs, a suitable diet, clean bedding, and the sense that care was always at hand. Other procedures used to help patients included the Mass, prayers, relics of saints, and music used to calm a troubled mind or quickened pulse.

Women

In 1376, in Sicily, it was historically given, in relationship to the laws of Federico II that they foresaw an examination with a regal errand of physicists, the first qualification to the exercise of the medicine to a woman, Virdimura a Jewess of Catania, whose document is preserved in Palermo to the Italian national archives.

Renaissance to Early Modern period 16th–18th century

The Renaissance brought an intense focus on scholarship to Christian Europe. A major effort to translate the Arabic and Greek scientific works into Latin emerged. Europeans gradually became experts not only in the ancient writings of the Romans and Greeks, but in the contemporary writings of Islamic scientists. During the later centuries of the Renaissance came an increase in experimental investigation, particularly in the field of dissection and body examination, thus advancing our knowledge of human anatomy.

The development of modern neurology began in the 16th century in Italy and France with Niccolò Massa, Jean Fernel, Jacques Dubois and Andreas Vesalius. Vesalius described in detail the anatomy of the brain and other organs; he had little knowledge of the brain's function, thinking that it resided mainly in the ventricles. Over his lifetime he corrected over 200 of Galen's mistakes. Understanding of medical sciences and diagnosis improved, but with little direct benefit to health care. Few effective drugs existed, beyond opium and quinine. Folklore cures and potentially poisonous metal-based compounds were popular treatments. Independently from Ibn al-Nafis, Michael Servetus rediscovered the pulmonary circulation, but this discovery did not reach the public because it was written down for the first time in the "Manuscript of Paris" in 1546, and later published in the theological work which he paid with his life in 1553. Later this was perfected by Renaldus Columbus and Andrea Cesalpino. Later William Harvey correctly described the circulatory system. The most useful tomes in medicine used both by students and expert physicians were De Materia Medica and Pharmacopoeia.

Bacteria and protists were first observed with a microscope by Antonie van Leeuwenhoek in 1676, initiating the scientific field of microbiology.

Paracelsus

Paracelsus (1493–1541), was an erratic and abusive innovator who rejected Galen and bookish knowledge, calling for experimental research, with heavy doses of mysticism, alchemy and magic mixed in. He rejected sacred magic (miracles) under Church auspisces and looked for cures in nature. He preached but he also pioneered the use of chemicals and minerals in medicine. His hermetical views were that sickness and health in the body relied on the harmony of man (microcosm) and Nature (macrocosm). He took an approach different from those before him, using this analogy not in the manner of soul-purification but in the manner that humans must have certain balances of minerals in their bodies, and that certain illnesses of the body had chemical remedies that could cure them. Most of his influence came after his death. Paracelsus is a highly controversial figure in the history of medicine, with most experts hailing him as a Father of Modern Medicine for shaking off religious orthodoxy and inspiring many researchers; others say he was a mystic more than a scientist and downplay his importance.

Padua and Bologna

University training of physicians began in the 13th century.

The University of Padua was founded about 1220 by walkouts from the University of Bologna, and began teaching medicine in 1222. It played a leading role in the identification and treatment of diseases and ailments, specializing in autopsies and the inner workings of the body. Starting in 1595, Padua's famous anatomical theatre drew artists and scientists studying the human body during public dissections. The intensive study of Galen led to critiques of Galen modeled on his own writing, as in the first book of Vesalius's De humani corporis fabrica. Andreas Vesalius held the chair of Surgery and Anatomy (explicator chirurgiae) and in 1543 published his anatomical discoveries in De Humani Corporis Fabrica. He portrayed the human body as an interdependent system of organ groupings. The book triggered great public interest in dissections and caused many other European cities to establish anatomical theatres.

At the University of Bologna the training of physicians began in 1219. The Italian city attracted students from across Europe. Taddeo Alderotti built a tradition of medical education that established the characteristic features of Italian learned medicine and was copied by medical schools elsewhere. Turisanus (d. 1320) was his student. The curriculum was revised and strengthened in 1560–1590. A representative professor was Julius Caesar Aranzi (Arantius) (1530–89). He became Professor of Anatomy and Surgery at the University of Bologna in 1556, where he established anatomy as a major branch of medicine for the first time. Aranzi combined anatomy with a description of pathological processes, based largely on his own research, Galen, and the work of his contemporary Italians. Aranzi discovered the 'Nodules of Aranzio' in the semilunar valves of the heart and wrote the first description of the superior levator palpebral and the coracobrachialis muscles. His books (in Latin) covered surgical techniques for many conditions, including hydrocephalus, nasal polyp, goitre and tumours to phimosis, ascites, haemorrhoids, anal abscess and fistulae.

Women

Catholic women played large roles in health and healing in medieval and early modern Europe. A life as a nun was a prestigious role; wealthy families provided dowries for their daughters, and these funded the convents, while the nuns provided free nursing care for the poor.

The Catholic elites provided hospital services because of their theology of salvation that good works were the route to heaven. The Protestant reformers rejected the notion that rich men could gain God's grace through good works—and thereby escape purgatory—by providing cash endowments to charitable institutions. They also rejected the Catholic idea that the poor patients earned grace and salvation through their suffering. Protestants generally closed all the convents and most of the hospitals, sending women home to become housewives, often against their will. On the other hand, local officials recognized the public value of hospitals, and some were continued in Protestant lands, but without monks or nuns and in the control of local governments.

In London, the crown allowed two hospitals to continue their charitable work, under nonreligious control of city officials. The convents were all shut down but Harkness finds that women—some of them former nuns—were part of a new system that delivered essential medical services to people outside their family. They were employed by parishes and hospitals, as well as by private families, and provided nursing care as well as some medical, pharmaceutical, and surgical services.

Meanwhile, in Catholic lands such as France, rich families continued to fund convents and monasteries, and enrolled their daughters as nuns who provided free health services to the poor. Nursing was a religious role for the nurse, and there was little call for science.

Age of Enlightenment

During the Age of Enlightenment, the 18th-century, science was held in high esteem and physicians upgraded their social status by becoming more scientific. The health field was crowded with self-trained barber-surgeons, apothecaries, midwives, drug peddlers, and charlatans.

Across Europe medical schools relied primarily on lectures and readings. The final year student would have limited clinical experience by trailing the professor through the wards. Laboratory work was uncommon, and dissections were rarely done because of legal restrictions on cadavers. Most schools were small, and only Edinburgh, Scotland, with 11,000 alumni, produced large numbers of graduates.

Britain

In Britain, there were but three small hospitals after 1550. Pelling and Webster estimate that in London in the 1580 to 1600 period, out of a population of nearly 200,000 people, there were about 500 medical practitioners. Nurses and midwives are not included. There were about 50 physicians, 100 licensed surgeons, 100 apothecaries, and 250 additional unlicensed practitioners. In the last category about 25% were women. All across Britain—and indeed all of the world—the vast majority of the people in city, town or countryside depended for medical care on local amateurs with no professional training but with a reputation as wise healers who could diagnose problems and advise sick people what to do—and perhaps set broken bones, pull a tooth, give some traditional herbs or brews or perform a little magic to cure what ailed them.

The London Dispensary opened in 1696, the first clinic in the British Empire to dispense medicines to poor sick people. The innovation was slow to catch on, but new dispensaries were open in the 1770s. In the colonies, small hospitals opened in Philadelphia in 1752, New York in 1771, and Boston (Massachusetts General Hospital) in 1811.

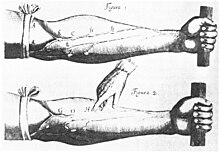

Guy's Hospital, the first great British hospital opened in 1721 in London, with funding from businessman Thomas Guy. In 1821 a bequest of £200,000 by William Hunt in 1829 funded expansion for an additional hundred beds. Samuel Sharp (1709–78), a surgeon at Guy's Hospital, from 1733 to 1757, was internationally famous; his A Treatise on the Operations of Surgery (1st ed., 1739), was the first British study focused exclusively on operative technique.

English physician Thomas Percival (1740–1804) wrote a comprehensive system of medical conduct, Medical Ethics, or a Code of Institutes and Precepts, Adapted to the Professional Conduct of Physicians and Surgeons (1803) that set the standard for many textbooks.

Spain and Spanish Empire

In the Spanish Empire, the viceregal capital of Mexico City was a site of medical training for physicians and the creation of hospitals. Epidemic disease had decimated indigenous populations starting with the early sixteenth-century Spanish conquest of the Aztec empire, when a black auxiliary in the armed forces of conqueror Hernán Cortés, with an active case of smallpox, set off a virgin land epidemic among indigenous peoples, Spanish allies and enemies alike. Aztec emperor Cuitlahuac died of smallpox. Disease was a significant factor in the Spanish conquest elsewhere as well.

Medical education instituted at the Royal and Pontifical University of Mexico chiefly served the needs of urban elites. Male and female curanderos or lay practitioners, attended to the ills of the popular classes. The Spanish crown began regulating the medical profession just a few years after the conquest, setting up the Royal Tribunal of the Protomedicato, a board for licensing medical personnel in 1527. Licensing became more systematic after 1646 with physicians, druggists, surgeons, and bleeders requiring a license before they could publicly practice. Crown regulation of medical practice became more general in the Spanish empire.

Elites and the popular classes alike called on divine intervention in personal and society-wide health crises, such as the epidemic of 1737. The intervention of the Virgin of Guadalupe was depicted in a scene of dead and dying Indians, with elites on their knees praying for her aid. In the late eighteenth century, the crown began implementing secularizing policies on the Iberian peninsula and its overseas empire to control disease more systematically and scientifically.

19th century: Rise of modern medicine

The practice of medicine changed in the face of rapid advances in science, as well as new approaches by physicians. Hospital doctors began much more systematic analysis of patients' symptoms in diagnosis. Among the more powerful new techniques were anaesthesia, and the development of both antiseptic and aseptic operating theatres.Effective cures were developed for certain endemic infectious diseases. However the decline in many of the most lethal diseases was due more to improvements in public health and nutrition than to advances in medicine.

Medicine was revolutionized in the 19th century and beyond by advances in chemistry, laboratory techniques, and equipment. Old ideas of infectious disease epidemiology were gradually replaced by advances in bacteriology and virology.

Germ theory and bacteriology

In the 1830s in Italy, Agostino Bassi traced the silkworm disease muscardine to microorganisms. Meanwhile, in Germany, Theodor Schwann led research on alcoholic fermentation by yeast, proposing that living microorganisms were responsible. Leading chemists, such as Justus von Liebig, seeking solely physicochemical explanations, derided this claim and alleged that Schwann was regressing to vitalism.

In 1847 in Vienna, Ignaz Semmelweis (1818–1865), dramatically reduced the death rate of new mothers (due to childbed fever) by requiring physicians to clean their hands before attending childbirth, yet his principles were marginalized and attacked by professional peers. At that time most people still believed that infections were caused by foul odors called miasmas.

Eminent French scientist Louis Pasteur confirmed Schwann's fermentation experiments in 1857 and afterwards supported the hypothesis that yeast were microorganisms. Moreover, he suggested that such a process might also explain contagious disease. In 1860, Pasteur's report on bacterial fermentation of butyric acid motivated fellow Frenchman Casimir Davaine to identify a similar species (which he called bacteridia) as the pathogen of the deadly disease anthrax. Others dismissed "bacteridia" as a mere byproduct of the disease. British surgeon Joseph Lister, however, took these findings seriously and subsequently introduced antisepsis to wound treatment in 1865.

German physician Robert Koch, noting fellow German Ferdinand Cohn's report of a spore stage of a certain bacterial species, traced the life cycle of Davaine's bacteridia, identified spores, inoculated laboratory animals with them, and reproduced anthrax—a breakthrough for experimental pathology and germ theory of disease. Pasteur's group added ecological investigations confirming spores' role in the natural setting, while Koch published a landmark treatise in 1878 on the bacterial pathology of wounds. In 1881, Koch reported discovery of the "tubercle bacillus", cementing germ theory and Koch's acclaim.

Upon the outbreak of a cholera epidemic in Alexandria, Egypt, two medical missions went to investigate and attend the sick, one was sent out by Pasteur and the other led by Koch. Koch's group returned in 1883, having successfully discovered the cholera pathogen. In Germany, however, Koch's bacteriologists had to vie against Max von Pettenkofer, Germany's leading proponent of miasmatic theory. Pettenkofer conceded bacteria's casual involvement, but maintained that other, environmental factors were required to turn it pathogenic, and opposed water treatment as a misdirected effort amid more important ways to improve public health.The massive cholera epidemic in Hamburg in 1892 devastasted Pettenkoffer's position, and yielded German public health to "Koch's bacteriology".

On losing the 1883 rivalry in Alexandria, Pasteur switched research direction, and introduced his third vaccine—rabies vaccine—the first vaccine for humans since Jenner's for smallpox. From across the globe, donations poured in, funding the founding of Pasteur Institute, the globe's first biomedical institute, which opened in 1888. Along with Koch's bacteriologists, Pasteur's group—which preferred the term microbiology—led medicine into the new era of "scientific medicine" upon bacteriology and germ theory. Accepted from Jakob Henle, Koch's steps to confirm a species' pathogenicity became famed as "Koch's postulates". Although his proposed tuberculosis treatment, tuberculin, seemingly failed, it soon was used to test for infection with the involved species. In 1905, Koch was awarded the Nobel Prize in Physiology or Medicine, and remains renowned as the founder of medical microbiology.

Women

Women as nurses

Women had always served in ancillary roles, and as midwives and healers. The professionalization of medicine forced them increasingly to the sidelines. As hospitals multiplied they relied in Europe on orders of Roman Catholic nun-nurses, and German Protestant and Anglican deaconesses in the early 19th century. They were trained in traditional methods of physical care that involved little knowledge of medicine. The breakthrough to professionalization based on knowledge of advanced medicine was led by Florence Nightingale in England. She resolved to provide more advanced training than she saw on the Continent. At Kaiserswerth, where the first German nursing schools were founded in 1836 by Theodor Fliedner, she said, "The nursing was nil and the hygiene horrible.") Britain's male doctors preferred the old system, but Nightingale won out and her Nightingale Training School opened in 1860 and became a model. The Nightingale solution depended on the patronage of upper class women, and they proved eager to serve. Royalty became involved. In 1902 the wife of the British king took control of the nursing unit of the British army, became its president, and renamed it after herself as the Queen Alexandra's Royal Army Nursing Corps; when she died the next queen became president. Today its Colonel In Chief is Sophie, Countess of Wessex, the daughter-in-law of Queen Elizabeth II. In the United States, upper middle class women who already supported hospitals promoted nursing. The new profession proved highly attractive to women of all backgrounds, and schools of nursing opened in the late 19th century. They soon a function of large hospitals, where they provided a steady stream of low-paid idealistic workers. The International Red Cross began operations in numerous countries in the late 19th century, promoting nursing as an ideal profession for middle class women.

The Nightingale model was widely copied. Linda Richards (1841–1930) studied in London and became the first professionally trained American nurse. She established nursing training programs in the United States and Japan, and created the first system for keeping individual medical records for hospitalized patients. The Russian Orthodox Church sponsored seven orders of nursing sisters in the late 19th century. They ran hospitals, clinics, almshouses, pharmacies, and shelters as well as training schools for nurses. In the Soviet era (1917–1991), with the aristocratic sponsors gone, nursing became a low-prestige occupation based in poorly maintained hospitals.

Women as physicians

It was very difficult for women to become doctors in any field before the 1970s. Elizabeth Blackwell (1821–1910) became the first woman to formally study and practice medicine in the United States. She was a leader in women's medical education. While Blackwell viewed medicine as a means for social and moral reform, her student Mary Putnam Jacobi (1842–1906) focused on curing disease. At a deeper level of disagreement, Blackwell felt that women would succeed in medicine because of their humane female values, but Jacobi believed that women should participate as the equals of men in all medical specialties using identical methods, values and insights. In the Soviet Union although the majority of medical doctors were women, they were paid less than the mostly male factory workers.

Paris

Paris (France) and Vienna were the two leading medical centers on the Continent in the era 1750–1914.

In the 1770s–1850s Paris became a world center of medical research and teaching. The "Paris School" emphasized that teaching and research should be based in large hospitals and promoted the professionalization of the medical profession and the emphasis on sanitation and public health. A major reformer was Jean-Antoine Chaptal (1756–1832), a physician who was Minister of Internal Affairs. He created the Paris Hospital, health councils, and other bodies.

Louis Pasteur (1822–1895) was one of the most important founders of medical microbiology. He is remembered for his remarkable breakthroughs in the causes and preventions of diseases. His discoveries reduced mortality from puerperal fever, and he created the first vaccines for rabies and anthrax. His experiments supported the germ theory of disease. He was best known to the general public for inventing a method to treat milk and wine in order to prevent it from causing sickness, a process that came to be called pasteurization. He is regarded as one of the three main founders of microbiology, together with Ferdinand Cohn and Robert Koch. He worked chiefly in Paris and in 1887 founded the Pasteur Institute there to perpetuate his commitment to basic research and its practical applications. As soon as his institute was created, Pasteur brought together scientists with various specialties. The first five departments were directed by Emile Duclaux (general microbiology research) and Charles Chamberland (microbe research applied to hygiene), as well as a biologist, Ilya Ilyich Mechnikov (morphological microbe research) and two physicians, Jacques-Joseph Grancher (rabies) and Emile Roux (technical microbe research). One year after the inauguration of the Institut Pasteur, Roux set up the first course of microbiology ever taught in the world, then entitled Cours de Microbie Technique (Course of microbe research techniques). It became the model for numerous research centers around the world named "Pasteur Institutes."

Vienna

The First Viennese School of Medicine, 1750–1800, was led by the Dutchman Gerard van Swieten (1700–1772), who aimed to put medicine on new scientific foundations – promoting unprejudiced clinical observation, botanical and chemical research, and introducing simple but powerful remedies. When the Vienna General Hospital opened in 1784, it at once became the world's largest hospital and physicians acquired a facility that gradually developed into the most important research centre. Progress ended with the Napoleonic wars and the government shutdown in 1819 of all liberal journals and schools; this caused a general return to traditionalism and eclecticism in medicine.

Vienna was the capital of a diverse empire and attracted not just Germans but Czechs, Hungarians, Jews, Poles and others to its world-class medical facilities. After 1820 the Second Viennese School of Medicine emerged with the contributions of physicians such as Carl Freiherr von Rokitansky, Josef Škoda, Ferdinand Ritter von Hebra, and Ignaz Philipp Semmelweis. Basic medical science expanded and specialization advanced. Furthermore, the first dermatology, eye, as well as ear, nose, and throat clinics in the world were founded in Vienna. The textbook of ophthalmologist Georg Joseph Beer (1763–1821) Lehre von den Augenkrankheiten combined practical research and philosophical speculations, and became the standard reference work for decades.

Berlin

After 1871 Berlin, the capital of the new German Empire, became a leading center for medical research. Robert Koch (1843–1910) was a representative leader. He became famous for isolating Bacillus anthracis(1877), the Tuberculosis bacillus (1882) and Vibrio cholerae (1883) and for his development of Koch's postulates. He was awarded the Nobel Prize in Physiology or Medicine in 1905 for his tuberculosis findings. Koch is one of the founders of microbiology, inspiring such major figures as Paul Ehrlich and Gerhard Domagk.

U.S. Civil War

In the American Civil War (1861–65), as was typical of the 19th century, more soldiers died of disease than in battle, and even larger numbers were temporarily incapacitated by wounds, disease and accidents. Conditions were poor in the Confederacy, where doctors and medical supplies were in short supply. The war had a dramatic long-term impact on medicine in the U.S., from surgical technique to hospitals to nursing and to research facilities. Weapon development -particularly the appearance of Springfield Model 1861, mass-produced and much more accurate than muskets led to generals underestimating the risks of long range rifle fire; risks exemplified in the death of John Sedgwick and the disastrous Pickett's Charge. The rifles could shatter bone forcing amputation and longer ranges meant casualties were sometimes not quickly found. Evacuation of the wounded from Second Battle of Bull Run took a week. As in earlier wars, untreated casualties sometimes survived unexpectedly due to maggots debriding the wound -an observation which led to the surgical use of maggots -still a useful method in the absence of effective antibiotics.

The hygiene of the training and field camps was poor, especially at the beginning of the war when men who had seldom been far from home were brought together for training with thousands of strangers. First came epidemics of the childhood diseases of chicken pox, mumps, whooping cough, and, especially, measles. Operations in the South meant a dangerous and new disease environment, bringing diarrhea, dysentery, typhoid fever, and malaria. There were no antibiotics, so the surgeons prescribed coffee, whiskey, and quinine. Harsh weather, bad water, inadequate shelter in winter quarters, poor policing of camps, and dirty camp hospitals took their toll.

This was a common scenario in wars from time immemorial, and conditions faced by the Confederate army were even worse. The Union responded by building army hospitals in every state. What was different in the Union was the emergence of skilled, well-funded medical organizers who took proactive action, especially in the much enlarged United States Army Medical Department, and the United States Sanitary Commission, a new private agency. Numerous other new agencies also targeted the medical and morale needs of soldiers, including the United States Christian Commission as well as smaller private agencies.

The U.S. Army learned many lessons and in August 1886, it established the Hospital Corps.

Statistical methods

A major breakthrough in epidemiology came with the introduction of statistical maps and graphs. They allowed careful analysis of seasonality issues in disease incidents, and the maps allowed public health officials to identify critical loci for the dissemination of disease. John Snow in London developed the methods. In 1849, he observed that the symptoms of cholera, which had already claimed around 500 lives within a month, were vomiting and diarrhoea. He concluded that the source of contamination must be through ingestion, rather than inhalation as was previously thought. It was this insight that resulted in the removal of The Pump On Broad Street, after which deaths from cholera plummeted afterwards. English nurse Florence Nightingale pioneered analysis of large amounts of statistical data, using graphs and tables, regarding the condition of thousands of patients in the Crimean War to evaluate the efficacy of hospital services. Her methods proved convincing and led to reforms in military and civilian hospitals, usually with the full support of the government.

By the late 19th and early 20th century English statisticians led by Francis Galton, Karl Pearson and Ronald Fisher developed the mathematical tools such as correlations and hypothesis tests that made possible much more sophisticated analysis of statistical data.

During the U.S. Civil War the Sanitary Commission collected enormous amounts of statistical data, and opened up the problems of storing information for fast access and mechanically searching for data patterns. The pioneer was John Shaw Billings (1838–1913). A senior surgeon in the war, Billings built the Library of the Surgeon General's Office (now the National Library of Medicine), the centerpiece of modern medical information systems. Billings figured out how to mechanically analyze medical and demographic data by turning facts into numbers and punching the numbers onto cardboard cards that could be sorted and counted by machine. The applications were developed by his assistant Herman Hollerith; Hollerith invented the punch card and counter-sorter system that dominated statistical data manipulation until the 1970s. Hollerith's company became International Business Machines (IBM) in 1911.

Worldwide dissemination

United States

Johns Hopkins Hospital, founded in 1889, originated several modern medical practices, including residency and rounds.

Japan

European ideas of modern medicine were spread widely through the world by medical missionaries, and the dissemination of textbooks. Japanese elites enthusiastically embraced Western medicine after the Meiji Restoration of the 1860s. However they had been prepared by their knowledge of the Dutch and German medicine, for they had some contact with Europe through the Dutch. Highly influential was the 1765 edition of Hendrik van Deventer's pioneer work Nieuw Ligt ("A New Light") on Japanese obstetrics, especially on Katakura Kakuryo's publication in 1799 of Sanka Hatsumo ("Enlightenment of Obstetrics"). A cadre of Japanese physicians began to interact with Dutch doctors, who introduced smallpox vaccinations. By 1820 Japanese ranpô medical practitioners not only translated Dutch medical texts, they integrated their readings with clinical diagnoses. These men became leaders of the modernization of medicine in their country. They broke from Japanese traditions of closed medical fraternities and adopted the European approach of an open community of collaboration based on expertise in the latest scientific methods.

Kitasato Shibasaburō (1853–1931) studied bacteriology in Germany under Robert Koch. In 1891 he founded the Institute of Infectious Diseases in Tokyo, which introduced the study of bacteriology to Japan. He and French researcher Alexandre Yersin went to Hong Kong in 1894, where; Kitasato confirmed Yersin's discovery that the bacterium Yersinia pestis is the agent of the plague. In 1897 he isolates and described the organism that caused dysentery. He became the first dean of medicine at Keio University, and the first president of the Japan Medical Association.

Japanese physicians immediately recognized the values of X-Rays. They were able to purchase the equipment locally from the Shimadzu Company, which developed, manufactured, marketed, and distributed X-Ray machines after 1900. Japan not only adopted German methods of public health in the home islands, but implemented them in its colonies, especially Korea and Taiwan, and after 1931 in Manchuria. A heavy investment in sanitation resulted in a dramatic increase of life expectancy.

Psychiatry

Until the nineteenth century, the care of the insane was largely a communal and family responsibility rather than a medical one. The vast majority of the mentally ill were treated in domestic contexts with only the most unmanageable or burdensome likely to be institutionally confined. This situation was transformed radically from the late eighteenth century as, amid changing cultural conceptions of madness, a new-found optimism in the curability of insanity within the asylum setting emerged.Increasingly, lunacy was perceived less as a physiological condition than as a mental and moral one to which the correct response was persuasion, aimed at inculcating internal restraint, rather than external coercion. This new therapeutic sensibility, referred to as moral treatment, was epitomised in French physician Philippe Pinel's quasi-mythological unchaining of the lunatics of the Bicêtre Hospital in Paris and realised in an institutional setting with the foundation in 1796 of the Quaker-run York Retreat in England.

From the early nineteenth century, as lay-led lunacy reform movements gained in influence, ever more state governments in the West extended their authority and responsibility over the mentally ill. Small-scale asylums, conceived as instruments to reshape both the mind and behaviour of the disturbed, proliferated across these regions. By the 1830s, moral treatment, together with the asylum itself, became increasingly medicalised and asylum doctors began to establish a distinct medical identity with the establishment in the 1840s of associations for their members in France, Germany, the United Kingdom and America, together with the founding of medico-psychological journals. Medical optimism in the capacity of the asylum to cure insanity soured by the close of the nineteenth century as the growth of the asylum population far outstripped that of the general population. Processes of long-term institutional segregation, allowing for the psychiatric conceptualisation of the natural course of mental illness, supported the perspective that the insane were a distinct population, subject to mental pathologies stemming from specific medical causes. As degeneration theory grew in influence from the mid-nineteenth century, heredity was seen as the central causal element in chronic mental illness, and, with national asylum systems overcrowded and insanity apparently undergoing an inexorable rise, the focus of psychiatric therapeutics shifted from a concern with treating the individual to maintaining the racial and biological health of national populations.

Emil Kraepelin (1856–1926) introduced new medical categories of mental illness, which eventually came into psychiatric usage despite their basis in behavior rather than pathology or underlying cause. Shell shock among frontline soldiers exposed to heavy artillery bombardment was first diagnosed by British Army doctors in 1915. By 1916, similar symptoms were also noted in soldiers not exposed to explosive shocks, leading to questions as to whether the disorder was physical or psychiatric. In the 1920s surrealist opposition to psychiatry was expressed in a number of surrealist publications. In the 1930s several controversial medical practices were introduced including inducing seizures (by electroshock, insulin or other drugs) or cutting parts of the brain apart (leucotomy or lobotomy). Both came into widespread use by psychiatry, but there were grave concerns and much opposition on grounds of basic morality, harmful effects, or misuse.

In the 1950s new psychiatric drugs, notably the antipsychotic chlorpromazine, were designed in laboratories and slowly came into preferred use. Although often accepted as an advance in some ways, there was some opposition, due to serious adverse effects such as tardive dyskinesia. Patients often opposed psychiatry and refused or stopped taking the drugs when not subject to psychiatric control. There was also increasing opposition to the use of psychiatric hospitals, and attempts to move people back into the community on a collaborative user-led group approach ("therapeutic communities") not controlled by psychiatry. Campaigns against masturbation were done in the Victorian era and elsewhere. Lobotomy was used until the 1970s to treat schizophrenia. This was denounced by the anti-psychiatric movement in the 1960s and later.

Siglo XX y más allá

Guerra y medicina del siglo XX

El sistema de grupo sanguíneo ABO fue descubierto en 1901, y el sistema de grupo sanguíneo Rhesus en 1937, lo que facilitó la transfusión de sangre.

Durante el siglo 20, las guerras a gran escala fueron atendidas con médicos y unidades de hospitales móviles que desarrollaron técnicas avanzadas para la curación de lesiones masivas y el control de las infecciones desenfrenadas en las condiciones del campo de batalla. Durante la Revolución mexicana (1910-1920), el general Pancho Villa organizó trenes hospitalarios para soldados heridos. Vagones marcados Servicio Sanitario ("servicio sanitario") fueron reubicados como quirófanos quirúrgicos y áreas de recuperación, y atendidos por hasta 40 médicos mexicanos y estadounidenses. Los soldados gravemente heridos fueron transportados de regreso a los hospitales base. El médico canadiense Norman Bethune, MD desarrolló un servicio móvil de transfusión de sangre para operaciones de primera línea en la Guerra Civil Española (1936-1939), pero irónicamente, él mismo murió de envenenamiento de la sangre. Miles de tropas con cicatrices proporcionaron la necesidad de mejores miembros protésicos y técnicas ampliadas en cirugía plástica o cirugía reconstructiva. Esas prácticas se combinaron para ampliar la cirugía estética y otras formas de cirugía electiva.

Durante la Primera Guerra Mundial, Alexis Carrel y Henry Dakin desarrollaron el método Carrel-Dakin de tratamiento de heridas con un riego, la solución de Dakin, un germicida que ayudó a prevenir la gangrena.

La Gran Guerra estimuló el uso de la radiografía de Roentgen y el electrocardiógrafo para el control de las funciones corporales internas. Esto fue seguido en el período de entreguerras por el desarrollo de los primeros agentes antibacterianos, como los antibióticos sulfa.

Salud pública

Las medidas de salud pública se volvieron especialmente importantes durante la pandemia de gripe de 1918, que causó la muerte de al menos 50 millones de personas en todo el mundo. Se convirtió en un importante caso de estudio en epidemiología. Bristow muestra que hubo una respuesta de género de los cuidadores de salud a la pandemia en los Estados Unidos. Los médicos de sexo masculino no pudieron curar a los pacientes y se sintieron fracasados. Las enfermeras también vieron a sus pacientes morir, pero se enorgullecieron de su éxito en cumplir su función profesional de cuidar, ministrar, consolar y aliviar las últimas horas de sus pacientes, y ayudar a las familias de los pacientes a enfrentar también.

De 1917 a 1923, la Cruz Roja Americana se mudó a Europa con una batería de proyectos de salud infantil a largo plazo. Construyó y operó hospitales y clínicas, y organizó campañas antituberculosas y antitróficas. Una alta prioridad involucraba programas de salud infantil tales como clínicas, mejores espectáculos para bebés, áreas de juegos infantiles, campamentos de aire fresco y cursos para mujeres sobre higiene infantil. Cientos de médicos, enfermeras y profesionales del bienestar de los Estados Unidos administraron estos programas, que tenían como objetivo reformar la salud de los jóvenes europeos y remodelar la salud y el bienestar públicos europeos a lo largo de las líneas estadounidenses.

Segunda Guerra Mundial

Los avances en medicina marcaron una diferencia dramática para las tropas aliadas, mientras que los alemanes y especialmente los japoneses y chinos sufrieron una grave falta de medicinas, técnicas e instalaciones más nuevas. Harrison encuentra que las posibilidades de recuperación para un soldado de infantería británico malherido eran hasta 25 veces mejores que en la Primera Guerra Mundial. La razón fue que:

- "En 1944, la mayoría de las víctimas recibían tratamiento pocas horas después de las heridas, debido a la mayor movilidad de los hospitales de campaña y al uso extensivo de aviones como ambulancias. El cuidado de los enfermos y heridos también había sido revolucionado por nuevas tecnologías médicas, como la inmunización activa contra el tétanos, las sulfonamidas y la penicilina ".

Investigación médica nazi y japonesa

Unethical human subject research, and killing of patients with disabilities, peaked during the Nazi era, with Nazi human experimentation and Aktion T4 during the Holocaust as the most significant examples. Many of the details of these and related events were the focus of the Doctors' Trial. Subsequently, principles of medical ethics, such as the Nuremberg Code, were introduced to prevent a recurrence of such atrocities. After 1937, the Japanese Army established programs of biological warfare in China. In Unit 731, Japanese doctors and research scientists conducted large numbers of vivisections and experiments on human beings, mostly Chinese victims.

Malaria

Starting in World War II, DDT was used as insecticide to combat insect vectors carrying malaria, which was endemic in most tropical regions of the world. The first goal was to protect soldiers, but it was widely adopted as a public health device. In Liberia, for example, the United States had large military operations during the war and the U.S. Public Health Service began the use of DDT for indoor residual spraying (IRS) and as a larvicide, with the goal of controlling malaria in Monrovia, the Liberian capital. In the early 1950s, the project was expanded to nearby villages. In 1953, the World Health Organization(WHO) launched an antimalaria program in parts of Liberia as a pilot project to determine the feasibility of malaria eradication in tropical Africa. However these projects encountered a spate of difficulties that foreshadowed the general retreat from malaria eradication efforts across tropical Africa by the mid-1960s.

Post-World War II

The World Health Organization was founded in 1948 as a United Nations agency to improve global health. In most of the world, life expectancy has improved since then, and was about 67 years as of 2010, and well above 80 years in some countries. Eradication of infectious diseases is an international effort, and several new vaccines have been developed during the post-war years, against infections such as measles, mumps, several strains of influenza and human papilloma virus. The long-known vaccine against Smallpox finally eradicated the disease in the 1970s, and Rinderpest was wiped out in 2011. Eradication of polio is underway. Tissue culture is important for development of vaccines. Though the early success of antiviral vaccines and antibacterial drugs, antiviral drugs were not introduced until the 1970s. Through the WHO, the international community has developed a response protocol against epidemics, displayed during the SARS epidemic in 2003, the Influenza A virus subtype H5N1 from 2004, the Ebola virus epidemic in West Africa and onwards.

Como las enfermedades infecciosas se han vuelto menos letales, y las causas más comunes de muerte en los países desarrollados son ahora los tumores y las enfermedades cardiovasculares, estas condiciones han recibido una mayor atención en la investigación médica. El tabaquismo como causa de cáncer de pulmón se investigó por primera vez en la década de 1920, pero no fue ampliamente respaldado por publicaciones hasta la década de 1950. El tratamiento del cáncer se ha desarrollado con radioterapia, quimioterapia y oncología quirúrgica.

La terapia de rehidratación oral se ha utilizado ampliamente desde la década de 1970 para tratar el cólera y otras infecciones que inducen diarrea.

La revolución sexual incluyó la investigación tabú sobre la sexualidad humana, como los informes de Kinsey de 1948 y 1953, la invención de la anticoncepción hormonal y la normalización del aborto y la homosexualidad en muchos países. La planificación familiar ha promovido una transición demográfica en la mayor parte del mundo. Con amenazas de infecciones de transmisión sexual, entre ellas el VIH, el uso de la barrera anticonceptiva se ha convertido en un imperativo. La lucha contra el VIH ha mejorado los tratamientos antirretrovirales.

Las imágenes de rayos X fueron el primer tipo de imágenes médicas, y más tarde se dispuso de imágenes ultrasónicas, tomografías computarizadas, escaneo de RM y otros métodos de imágenes.

La genética ha avanzado con el descubrimiento de la molécula de ADN, el mapeo genético y la terapia génica. La investigación de células madre despegó en la década de 2000 (década), con la terapia de células madre como un método prometedor.

La medicina basada en la evidencia es un concepto moderno que no se introdujo en la literatura hasta los años noventa.

Las prótesis han mejorado. En 1958, Arne Larsson en Suecia se convirtió en el primer paciente en depender de un marcapasos cardiaco artificial. Murió en 2001 a la edad de 86 años, habiendo sobrevivido a su inventor, el cirujano, y 26 marcapasos. Los materiales ligeros y las prótesis neuronales surgieron a fines del siglo XX.

Cirugía moderna

La cirugía cardíaca se revolucionó en 1948 cuando se introdujo la cirugía a corazón abierto por primera vez desde 1925.

En 1954, Joseph Murray, J. Hartwell Harrison y otros lograron el primer trasplante de riñón. Los trasplantes de otros órganos, como el corazón, el hígado y el páncreas, también se introdujeron a finales del siglo XX. El primer trasplante parcial de cara se realizó en 2005 y el primero fue completo en 2010. A finales del siglo XX, la microtecnología se había utilizado para crear diminutos dispositivos robóticos para ayudar a la microcirugía mediante el uso de cámaras de microvídeo y de fibra óptica para visualizar datos internos. tejidos durante la cirugía con prácticas mínimamente invasivas.

La cirugía laparoscópica fue ampliamente introducida en la década de 1990. La cirugía de orificios naturales ha seguido. La cirugía remota es otro desarrollo reciente, con la operación Lindbergh en 2001 como un ejemplo innovador.

Obtenido de: https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/History_of_medicine